Queenstown, where I spent the earliest days of my life, holds many wonderful memories for me. It is a place I enjoy going back to, which I regularly do in my attempts to rediscover memories the town holds of my childhood, discovering more often than not a fascinating side to Singapore’s first satellite town I had not known of before.

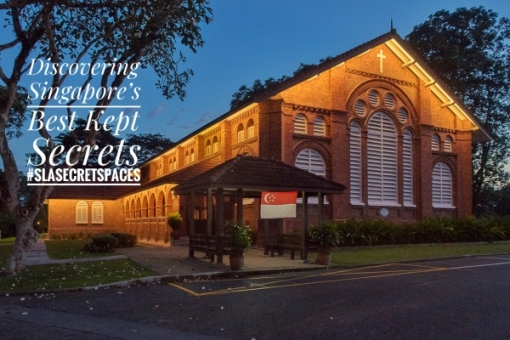

A window into a world in which one will discover the many layers of a rich and varied history.

A chance to revisit Queenstown and learn more about it came recently when I participated in an introductory My Queenstown heritage tour of Holland Village and Commonwealth. The tour, which started at Chip Bee Gardens, took a path that ended in the unreal world of palatial homes that lies just across the town’s fringes at Ridout Road. Intended to provide participants with a glimpse into the area’s evolution from its gambier and rubber plantation days to the current mix of residential, commercial and industrial sites we see today, it also provided me an opportunity to revisit the neighbourhood that I had spent my first three years in.

Jalan Merah Saga in Chip Bee Gardens.

Adjacent to an ever-evolving Holland Village, Chip Bee Gardens – the starting point, is known today for its eclectic mix of food and beverage outlets and businesses, housed in a rather quaint looking row at Jalan Merah Saga. Many from my generation will remember it for a crêpe restaurant, Better Betters. In combining French inspired crêpes with helpings of local favourites such as rendang, the restaurant married east and west in a fashion that seemed very much in keeping with the way the neighbourhood was developing.

A view over Chip Bee Gardens.

The shop lots, I was to learn, had rather different beginnings. Converted only in 1978, the lots had prior to the 1971 pull-out of British forces, served as messing facilities for the military personnel the estate had been built to accommodate in the 1950s. The growth of Holland Village into what it is today, is in fact tied to this development. Several businesses still found at Holland Village trace their roots back to this era.

Holland Road Shopping Centre, a familiar landmark in Holland Village.

The Thambi Magazine Store at Lorong Liput is one such business. Having its roots in the 1960s, when the grandfather of its current proprietor, delivered newspapers in the area, the so-called mama-shop, has grown to become a Holland Village institution. It would have been one of two such outlets found along Lorong Liput, previously occupying a space across from its current premises. Its well-stocked magazine racks once drew many from far and wide in search of a hard-to-find weekly and is now the sole survivor in an age where digital media dominates.

Sam, the current proprietor of the Thambi Magazine Store.

Magazine racks outside the store.

Lorong Liput would also have been where many of Holland Village’s landmarks of the past were once found. One was the Eng Wah open-air cinema, the site of which the very recently demolished Holland V Shopping Mall with its mock windmill – a more recent icon, had been built on. Lorong Liput was also where the demolished Kampong Holland Mosque once stood at the end of and where the old wet market, since rebuilt, served the area’s residents.

The windmill at Lorong Liput, which recently disappeared.

The rebuilt market.

The site of the former Eng Wah open-air cinema and the since demolished Holland V Shopping Mall.

From Lorong Liput, a short walk down Holland Avenue and and Holland Close, takes one to the next stop and back more than a century in time. The sight that greets the eye as one approaches the stop, which is just behind Block 32, is one that is rather strange of neatly ordered rows of uniformly sized grave stones of a 1887 Hakka Chinese cemetery, the Shuang Long Shan, set against a backdrop of blocks of HDB flats and industrial buildings. Visually untypical of an old Chinese cemetery – in which the scattering of burial mounds would seem almost random, the neat rows contain reburied remains from graves exhumed from an area twenty times the 4.5 acre plot that the cemetery once occupied.

A view across the grave stones to the roofs of the Shuang Long Shan Wu Shu ancestral hall.

Run by the Ying Fo Fui Kun clan association, Shuang Long Shan was acquired by the HDB in 1962. A concession made to the clan association permitted the current site to be retained on a lease. The site also contains the clan’s ancestral hall, the Shuang Long Shan Wu Shu Ancestral Hall and a newer memorial hall. The ancestral hall, which also goes back to 1887, is now the oldest building in Queenstown.

Offerings placed for the Ching Ming festival.

Ancestral tablets inside the hall.

A close-up of the ancestral hall.

My old neighbourhood nearby was up next. Here I discovered how easy it was to be led astray in finding myself popping into Sin Palace – one of the several old shops found in the neighbourhood centre in which time seems to have long stood still. The shops offer a fascinating glimpse of the world four, maybe five decades past, days when I frequented the centre for my favourite bowl of fishball noodles and the frequent visits to the general practitioner the coughs I seemed to catch would have required. The neighbourhood is where a rarity from a perspective of church buildings can be found in the form of the Queenstown Lutheran Church. It is one of few churches from the era that retains much of its original look.

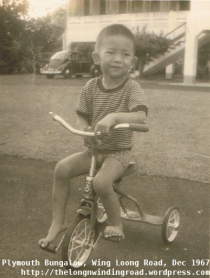

Commonwealth Crescent Neighbourhood Centre and the Lutheran Church as it looked when I lived there (source: My Community).

Inside Sin Palace – an old fashioned barber shop.

Another area familiar to me is the chap lak lau chu (16 storey flats) at Commonwealth Close, which we also visited. A friend of my mother’s who we would visit on occasion, lived there at Block 81, a block from which one can look forward to an exhilarating view from its perch atop a hillock. The view was what gave Block 81 the unofficial status of a “VIP block” to which visiting dignitaries would be brought to – much like the block in Toa Payoh to which I moved to. Among the visitors to the block were the likes of Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh and Indian Prime Minister Mrs. Indira Gandhi.

Also at Commonwealth Close, the space between Blocks 85 and 86 where the iconic photograph of Singapore’s first Prime Minister, Mr Lee Kuan Yew was taken.

Before visiting Block 81, a stop was made at Commonwealth Drive, where the MOE Heritage Centre and Singapore’s first flatted factories are found. The flatted factory, an idea borrowed from Hong Kong, allowed space for small manufacturers to be quickly and inexpensively created during the period of rapid industrialisation and the block at Commonwealth Drive (Block 115A) was the first to be constructed by the Economic Development Board (EDB) as part of a pilot programme launched in 1965 (more on the development of flatted factories in Singapore can be found on this post: The Anatomy of an Industrial Estate). Among the first tenants of the block were Roxy Electric Industries Ltd. The company took up 10,000 square metres on the ground floor for the assembly of Sharp television sets under licence.

Block 115 A (right) – the first flatted factory building that was erected by the EDB in 1965/66 as part of a pilot programme.

A resident of Queenstown, Mdm Noorsia Binte Abdul Gani, found work assembling hairdryers at an electrical goods factory, Wing Heng, between 1994 and 2003. Wing Heng was located at Block 115A Commonwealth Drive.

Housed in a school building typical of schools built in the 1960s used previously by Permaisura Primary School, the MOE Heritage Centre was established in 2011. With a total of 15 experiential galleries and heritage and connection zones arranged on the building’s three floors, the centre provides visitors with an appreciation of the development of education and schools in Singapore, from the first vernacular and mission schools to where we are today.

The MOE Heritage Centre.

A blast from the past – a schoolbag from days when I started attending school at the MOE Heritage Centre.

Of particular interest to me were the evolution of school architecture over the years and the post-war period in the early 1950s when many new schools and the Teachers’ Training College were established. The centre is opened to the public on Fridays during term time and on weekdays during school holidays. More information can be found at http://www.moeheritagecentre.sg/public-walk-ins.html.

Inside the MOE Heritage Centre’s New Nation, New Towns & New Schools gallery.

The Ridout Tea Garden lies across Queensway from the Commonwealth Close area. The garden rose out of the ashes of what many would remember as a Japanese styled garden, the Queenstown Japanese Garden. Opened in 1970, a few years before the Seiwaen in Jurong, the garden would have been the first post-independence Japanese styled public garden (the Alkaff Lake Gardens, which opened in 1930 would have been the first). A fire destroyed the garden in 1978 and the HDB redeveloped it as a garden with a teahouse (hence Tea Garden) tow years later. Well visited today for its McDonalds outlet, it was actually a Kentucky Fried Chicken outlet that first operated at the tea house.

A brick wall, which once belonged to the Japanese Garden.

The tea garden forms part of the boundary between Queenstown and a world that literally is apart at the Ridout Road/Holland Park conservation area. Home to palatial good class bungalows, 27 of which are conserved, many of the area’s houses have features that place them in the 1920s and the 1930s. This was the period which coincided with the expansion of the British military presence on the island, and it was during this time that the nearby Tanglin Barracks was built. Several, especially those in the mock Tudor or “Black and White” style – commonly employed by the Public Works Department, would have served to house senior military officers .

A mock Tudor bungalow at 31 Ridout Road.

Besides the “Black and White” style, another style that is in evidence in the area is that of the Arts and Crafts movement. Several fine examples of such designs exist on the island, two of which are National Monuments. One is the very grand Command House at Kheam Hock Road, designed by Frank W. Brewer. Brewer was also responsible for the lovely house found at 23 Ridout Road. Distinctly a Brewer design, the house had prior to the war, been the residence of L. W. Geddes. A board member of Wearnes Brothers and a Municipal Commissioner, Mr Geddes left Singapore upon his retirement in late 1941. After the war, the house was used as the Dutch Consul-General’s and later Ambassador’s residence.

Distinctively Frank W. Brewer – an Arts and Crafts design that was once the home of L.W. Geddes at 23 Ridout Road. The house now serves as the residence of the Dutch Ambassador.

A recent addition to the area is the mansion at 2 Peirce Drive. Owned by Dr. Lye Wai Choong, the house is thought to have been modelled after the Soonstead Mansion in Penang. Other notable bungalows in the area include 35 Ridout Road, which sold recently for S$91.69 million and also India House at 2 Peirce Road, thought to have been commissioned by Ong Sam Leong in 1911. Mr Ong, who made his fortune from being the sole supplier of labour to the phosphate mines on Christmas Island, passed away in 1918 and is buried with his wife in the largest grave in Bukit Brown cemetery.

A more recent addition to the area, a mansion owned by Dr. Lye Wai Choong, which is modelled after another one in Penang.

The good-class bungalow at 35 Ridout Road that was sold very recently for S$91.69 million.

A very green Ridout Road.

The Commonwealth and Holland Village heritage tour runs every third Sunday of the month. Those interested can register for the free guided tour at www.queenstown.evenbrite.sg or via myqueenstown@gmail.com. My Community, which runs the tours is also carrying out a volunteer recruitment exercise to run their tours. Workshops are being held on 24 and 30 April 2016 for this and would be volunteers can email volunteer@mycommunity.org.sg to register.