I must admit that there was a time when I would have been reluctant to set foot in a kampung (village) in Singapore being very much the urban kid that I was growing up in the new highrise village of Toa Payoh. Back in the early days of Toa Payoh, much of Singapore still lived in the attap and zinc roofed wooden houses set in the densely packed villages all over the rural parts of the island. I had myself, had several experiences of a kampung in my early days, having been made to visit a so-called “sworn-sister” of my maternal grandmother at least once every Chinese New Year when we would spend most of the second day at the chicken farm in Punggol which she and her husband had in their care.

Despite my reluctance to visit kampungs in my early childhood, kampung days were never far away with regular visits to one in Punggol.

The visits to Punggol would inevitably mean that I would have to bear a few hours of boredom, stuck in the confines of what served as the living and dining room of the house with the simple furnishings of a formica topped folding table, a few stools, a food cabinet, two armchairs, and a small coffee table to keep me company. All there was to break the monotony of the room would be the sound of the Rediffusion speaker breaking the relative silence of the room, as I impatiently waited for one of my parents to make an appearance. The great outdoors where my parents would invariably spend the first part of the visits at wasn’t something that I was exactly enamoured with, particularly the fresh country air that would be laced with the smells that came from the rows of chicken coops nearby, a mixture of the smell of chicken feed and chicken droppings, with that of the generous amounts of natural fertiliser that would be used on the numerous plots of vegetables growing around. The fascination that I had with some of the livestock certainly wouldn’t have been enough to presuade me to move from my perch on one of the stools, let alone step across the threshold to join my parents in admiring the ripening array of tropical fruits that awaited their harvest outside.

It certainly has been a long time since I last took in the sights of zinc roofed wooden house in Singapore.

Not all kampungs are made the same of course, and I certainly, as a casual visitor, appreciated some of the coastal villages a lot more than I did the one I regularly visited at Punggol. My earliest encounters with the villages by the seaside would have been at Mata Ikan and Ayer Gemuruh in my very early years, passing through on my hoildays around the Tanah Merah and Mata Ikan area. It only much later in life that I got to wander around some of them in earnest, with one on our northern shoreline just east of the Mata Jetty at the end of Sembawang Road, being one that I would visit often, Kampung Tanjong Irau. The coastal villages were usually more pleasing to the eyes, and it was always nice to encounter the often colourful sight of fishing boats ashore and fishing nets strung up to be mended. This sight would often be accompanied by the whiff of the sea that would be mixed with the smells left on the nets that the catch the nets had held, carried by the gentle breeze from the sea.

The smell of fishing nets was something to look forward to during visits in my childhood to the coastal villages which I seemed to enjoy more.

It was in the latter part of the 1980s that I started to lose touch with the kampungs that I knew, as the busy schedule of my tertiary education and National Service, as well as time spent away from Singapore, took me away from the routines that occupied my childhood. Distracted by what was going on in my life then and the years of my career, the opportunity to say goodbye to the villages of my youth had soon passed me by, as it was during that time that, one by one, the villages that had been very much a part of Singapore’s rural landscape started to disappear as modernisation in Singapore caught up with them. My grandmother’s “sworn-sister” had during that time, been forced to abandon the lifestyle she had known all her life and resettled in Ang Mo Kio, just a stone’s throw from where I lived.

Zinc roofs were once common all over rural Singapore and started to disappear with the wave of urbanisation that swept through rural Singapore in the 1980s.

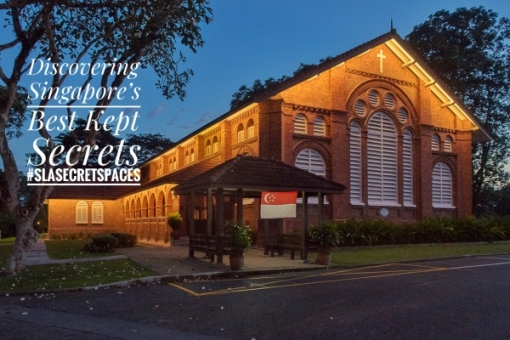

It was only well into the arrival of the new century that I realised that there had been one village, Kampung Lorong Buangkok, that had somehow resisted the tide of development that had swept through the island and it was in reading a New York Times article “Singapore Prepares to Gobble Up Its Last Village” in early 2009 that I had thought of having a look at what has been touted as the last remaining village on mainland Singapore. Having on many occasions cycled through the area during my teenage years, the village was actually tucked away in an area that was familiar to me, although it was the grounds of the road that led up to the mental hospital, Woodbridge Hospital, named after the main access road to the area, Jalan Woodbridge, that I took more notice of (Jalan Woodbridge has in the intervening years been renamed Gerald Drive in an effort by property developers to avoid any association housing developments in the area could have with the mental hospital (which has since moved to nearby Hougang and renamed as the Institute of Mental Health), but it wasn’t until the National Library Board organised a visit to the kampung recently that I got to have my look around.

The area around Gerald Drive bear very little resemblance to the road that I had once cycled around when it was called Jalan Woodbridge.

An old road sign with the old four digit postal code.

The visit was certainly one that was well worth the while, rather than having to explore the are on my own as besides navigating through the labyrinth that is the village, the guide, Mr Bill Gee, was able to also provide some information on the village as well. The village as it currently stands, sits on a one and a third hectare plot of land (equivalent to the size of three football fields) which is owned by a Ms Sng Mui Hong, a 57 year old resident of the village. Ms Sng had inherited the land from her father who had bought the land when she was three (in 1956), constructing a village which at its height occupied an area roughly twice its current size with 40 households living on it. Today, Ms Sng rents the zinc roofed housing units out to the 28 households that remain, keeping rents at levels that make the rents (by a long way) the cheapest on the island at between S$6.50 to S$30 (excluding electricity and water).

An address plate at a house along Lorong Buangkok where the last village on mainland Singapore stands.

A Chinese home at the entrance to the last village.

Lorong Buangkok as it looks today.

A well photograph sign points the way to the Surau (Muslim Prayer Room).

It certainly felt surreal walking through the kampung, especially in the context of what Singapore has become. The village did appear very much as if time has left it behind, as I weaved my way through the maze of wooden houses, each with a distinct character and colour. The houses were certainly typical of the kampung houses of old, with cemented floors and a grilled gap left between the zinc roofs and the exterior walls of wood to provide ventilation. Wood is used as a structural building material not just because that it is a traditional material, but also as the use of brick and mortar would render the houses too heavy to be supported by the soft muddy ground that lies below due to the area having once been a swamp which was fed by a creek upstream of Sungei Punggol, which my mother had been familiar with in her own childhood, as having lived at the sixth mile area of Upper Serangoon Road not far away, it was where as she would recall, “my father would jump into, not having a care in the world for the possible dangers that the waters held”, stopping the practice only after a mangrove snake had been spotted on one of their forays into the creek. There certainly still is some evidence of what was a brackish water swamp: mud lobster mounds and the red-brown petals of the flowers of the Sea Hibiscus tree are clearly visible on the ground in the area of the village just by what is now a canalised Sungei Punggol. Being built in a low-lying area where a swamp had formed, the village is also one that is prone to flooding, as the evidence – a flood level marker and a signboard providing information on days when there is a risk of flooding at road in from the main road, across from the well photographed sign giving directions to the village’s Surau (a Muslim prayer room), does suggest.

Mud Lobster mounds are clearly visible in the area near the canalised Sungei Punggol, bearing testament to the swamp that existed in the area.

The area is prone to flooding. A PUB signboard is used to inform villagers of days on which flooding is likely to occur.

A flood level marker is seen in the drain close to the PUB signboard.

In the vicinity of the village near where the flood level marker is, is the site of the former SILRA Home (a home for ex-Leprosy patients run by the SIngapore Leprosy Relief Association – hence SILRA) along Lorong Buangkok, of which the entrance remains with a wall on which the faint words “SILRA HOME” can be made out. The home moved to Buangkok View in 2004.

A wall is all that remains of the entrance to the former SILRA Home along Lorong Buangkok.

Many of the Malay and Chinese residents have lived in the village for well over forty years, with many not wanting to move out having been used to the laid back lifestyle and access to open spaces which moving into the modern suburbia would rob them of. It was certainly nice to encounter some of the villagers, who readily smiled at the curious group of visitors that had descended on the village breaking the calm and peace of the village, of whom I am sure they get too many of as interest in the last kampung has increased with all the publicity it has received in recent years. Peaceful the kampung certainly was compared to my first memories of the kampung in Punggol, where the were the sounds of the clucking of hens, the crowing of roosters, the quacking of ducks, the snorting and grunting of pigs and the barking of dogs never seemed to cease. It was in this sea of sounds that one which I would never forget would pierce through each evening – the unmistakable and shirll crescendo that was the chorus of pigs squealing as if they might have been singing for their supper.

The kampung's Surau.

The wooden houses each have a character of their own, painted in the different colours that add a certain charm to the village.

Other sights around Kampung Lorong Buangkok …

Modern times I guess have caught up with the last kampung - I mentioned my parents experience being the first in Kampong Chia Heng to own a TV in a previous post - back then, doors were unlocked and everyone in the village could walk into the living room to have a curious glance at the TV set.

A hinge for a gate ...

Clothes pegs on a laundry line.

A view through a set of bamboo blinds ...

A hibiscus in full bloom.

Ornamental flags flapping in the wind.

A resident on a bicycle.

Malay residents of the kampung.

The star of the kampung - a star made by Jamil Kamsah, a resident of the kampung.

A hurricane lamp ...

and another ...

One of the last places in Singapore to have cables overhead ...

A fallen fruit from a Starfruit tree ...

A Buddha statue.