It was an air of quiet calm that greeted me as I stepped into a room where the ghosts of a time we may otherwise have forgotten continue to haunt us. The room, bathed in the glow of light painted gold by the ochre of the walls the light reflected off, seemed to extend a warm welcome which it would have in the cold dark days when it offered hope when there might only have been despair.

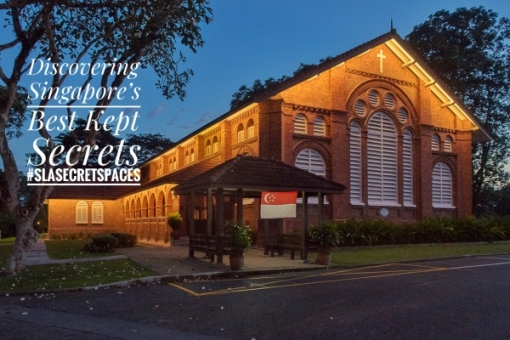

The Chapel of St. Luke on the ground floor of Block 151.

The room, converted into the makeshift Chapel of St. Luke (dedicated to St. Luke the physician) during the Japanese Occupation, was where a Prisoner-of-War (POW) by the name of Stanley Warren who held the rank of Bombardier in the Royal Artillery, weakened by a severe bout of renal disorder and dysentery, drew on whatever reserves he had left in strength, to decorate, remarkably, two of the chapel’s walls with five paintings of biblical scenes from the New Testament which along with the chapel became a light in the darkness of days uncertain.

The chapel and murals were a light in the darkness of captivity for prisoners during the dark days of World War II.

The chapel which occupies a room in what was Barrack Block 151 in Roberts Barracks, which together with the neighbouring barracks and nearby Changi Prison became an extended gaol that the Japanese forces used to hold the large numbers of POWs they held. Block 151 was made part of the gaol’s hospital becoming part of a dysentery wing which included several other surrounding buildings.

Block 151 is one of a few structures from WWII which remain in the area.

Another view of Block 151.

Even if not for the weakened state of the painter, putting the paintings we now know as the ‘Changi Murals’ on the walls would have required an incredible effort. Based on information provided by the expert guide Mr. Vickna, we were told of how paints, pigments and even brushes were in extremely short supply, and they had to be procured through whatever means available – some which may have even put the men involved at risk.

A photograph of the late Stanley Warren who passed away in 1992.

There was also a huge degree of improvisation involved – the colour blue for example, was obtained from crushing chalk used on billiard cues.

A map of the POW camp sketched by Stanley Warren.

Too ill to be sent to work on the Death Railway in Siam, which he is said to have said probably saved his life, Warren found himself recuperating in a ward above the chapel in 1942, Warren and many around him drew on the comfort provided by what could be heard of the strains of Merbecke’s arrangement of the Litany being sung in the chapel.

Mr Vickna the guide.

It was hearing the voices in song throughout his slow recovery which was to serve as an inspiration for Warren who was approached by the chaplain who knew of his artistic background to decorate the makeshift chapel. He struggled through the first, The Nativity, for over two months, managing to complete it in time for Christmas in 1942. Warren was to complete four more works – the last, a mural of St. Luke in Prison, was completed in May 1943.

The Nativity was the first mural painted. On a copy painted on a wallboard in 1963, Warren painted an albatross in place of the horse’s head.

A feature of the murals is how Warren also used it depict what he did see around him – many of the faces were those of his fellow POWs and in the third mural, The Crucifixion, which I thought was the most moving, we do also see slaves dressed in loincloths in the same way the men around him were dressed in their rags. The words found above the mural “Father forgive them for they know not what they do” were we were told also a reference to his captors and the slaves crucifying Christ being the “slaves” many of his captors were to authority.

The Ascension – the second mural.

The murals were initially thought to have been destroyed – the Japanese later converted the room into a storeroom and were thought to have broken down walls as well as painting over the remaining murals. They were thought to have been discovered by Royal Air Force (RAF) personnel in 1958 and a search was made through the press in the UK for the painter – the name Stanley Warren cropping up only when a short description of the chapel and a reference to the murals was found in a book “The Churches of Captivity in Malaya”, which was discovered in the Far East Air Force Educational Library in Changi.

The Crucifixion, the third mural which was partly damaged by a doorway made in the wall – the evidence of which can still be seen.

Then an art teacher in London, Warren was invited to restore the murals, first refusing to do so on the fear of having to confront the demons of the dark days in which he executed the work. He did eventually return after much soul searching – first just before Christmas in 1963, and then again in 1982 and 1988. One of the murals does remain unrestored – the last, the lower part of which was destroyed when the wall was knocked down by the Japanese.

The Last Supper – the fourth mural.

It was one for which Warren did not have a copy of his original sketch of (which was found in the possession of a fellow prisoner later in 1985), and decided to leave what remains of in its original condition. Warren did paint a copy of it, a photograph of which can be seen below the mural in which he replaced one of the figures he orginally painted.

The unrestored upper portion of the fifth mural, St. Luke in Prison.

The Crucifixion is also one which was partly destroyed when a doorway was made in the wall – the evidence of which can still be seen.

A copy of the fifth mural which Warren painted.

Another interesting fact was one that we did learn about The Nativity mural – it was thought to have been destroyed and a copy was painted on a wallboard which was eventually removed by the RAF. The copy was one on which Warren replaced the head of the horse found on the original work with an albatross to as a symbol of flying men of the RAF which was using the barracks at the time. A part the original mural – that of the horse’s head, was found by one of the boys from the Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) Boys School (which occupied the building in the 1980s) tasked with helping Warren to restore the murals in 1982.

A view of the chapel.

The work, which is said to have offered solace and hope to the many prisoners who used the chapel, is today a reminder not just of a event we should never again want to find ourselves confronting, but also one of the triumph of the human spirit in the face of adversity. The building which houses the chapel, lies today in a restricted area within the Republic of Singapore Air Force’s (RSAF) Changi Air Base (West) and I am grateful to MINDEF’s NS Policy Department and the RSAF for the opportunity to be moved by the murals in its original setting. A copy of the murals to which members of the public have access to, can be found in the Changi Museum.

The chapel offered hope where there seemed to have been none.

Mr Vickna speaking about The Ascension.

The corridor outside the chapel.

Information on Stanley Warren and the Changi Murals

- Infopedia on the Changi Murals

- Infopedia on Stanley Warren

- Detailed information on the Changi Murals

-

The Royal Anglian & Royal Lincolnshire Regimental Association *

- Australian War Memorial Site on the Changi Murals

* with photographs of it in the condition it when it was originally uncovered

[…] Blog at the Singapore Blog Awards in the past two years. He wrote a sombre account of his visit in A light where there was only darkness: The Changi Murals. Jerome kindly shares the precious Changi Murals images he took in my […]

It will be nice to be able to view the paintings. I frequently hear from my dad that he slept in the exact same room during his days serving the British Royal Air force. It was rumored to be haunted and the British soldiers dare not sleep in there. Nice write up.

In April 1973, I was a recruit in Platoon 3, Alpha Company, !st SBMT. My comrades and I were not aware that we were staying in such a famous block. One day, our platoon commander, before our passing out parade, Lta Hamid brought us into the room which was always locked and introduced us to the Changi Murals.

It was so beautiful and also show the spirit of the POWs that endure the sufferings of WW II.

This moment is deeply engraved in my mind.

Thank you so very much for this article and superb photography that bring to life such a time as this.

Thank you so much for a brilliant write up and letting us see the murals in their original setting. My husband was stationed their for two years in the early seventies and often spoke of them, lovely to see them. His uncle was a POW there and never coped with life after, lovely man and such a shame. Senseless brutality to such beautiful people!! Heartbreaking xx

I lived for years in block 151 in the early 50’s and really appreciated the murals