I’ve always enjoyed a bowl of laksa. The dish, which has an amazing range of equally delectable localised variations, brings great comfort and joy to many in Malaysia, parts of Indonesia and Singapore. There is perhaps no other dish that can so strongly be identified with a locality. In its very basic form, laksa is a vermicelli like noodle in a broth. While it can be said that it is in the countless variations of this broth, tempered by the influences of over a century, that has provided the various forms of the dish with its local flavour; its origins as a dish, how it morphed into what we see of it today, and even its rather strange sounding name, is a source of great puzzlement.

One suggestion of how laksa got its name that has gained popularity is that it was derived from a similar sounding Sanskrit word for a hundred thousand. This, it is said, is an allusion perhaps to the multitude of ingredients that go into making the various forms of its broth the celebration of flavours that they are. I am however inclined to take the side of the suggestion that the wonderful encyclopedia of the world’s culinary delights, the Oxford Companion to Food, offers. That has the word laksa being Persian in origin. Lakhsha meaning “slippery” in old Persian, was apparently also used to describe noodles, which the book also credits the Persians with the invention of.

Sarawak Laksa

That latter suggestion will no doubt spark endless debate. There seems however to be evidence to support the assertion such as in the many noodle type dishes that are found spread across the Middle East, Central Asia and Europe – all with names that all sound very much like lakhsha. Examples of this are the Russian lapsha, the Uyghur laghman, the Jewish lokshen, the Afghan lakhchak, the Lithunian Lakštiniai, and the Ukrainian lokshina. The Italian sheet pasta dish, Lasagne, also sounds uncannily similar to old Persian for noodles.

Lokshen (photo: Danny Nicholson on Flickr CC BY-ND 2.0).

As with the variants of the Near East, Lakhsha seems to have become a similiar sounding laksa in this part of the world. Early Malay-English dictionaries, such as one published by R. J. Wilkinson in 1901, have laksa both as the word for ten thousand, as well as for a “vermicelli” – ascribing the latter’s origins to the same Persian word. The use of the word as such is seen in several of the news articles of the day. One report, in the Malayan Saturday Post of 29 December 1928, shows how “Chinese Laksa” was then made, through a series of four photographs. As a word to describe a type of noodles, laksa is in fact very much still in use in places such as the Riau Archipelago. There, “lakse” or “laksa”, is taken as a noodle of a similar appearance to the laksa we find here made from the staple of the islands, sago.

R. J. Wilkinson’s “A Malay-English Dictionary” describes the word “laksa” both as a word for ten-thousand as well as for a kind of vermicelli.

There also are early descriptions of how that laksa may have been prepared in the press. One, found in a 1912 report on hawker fare in The Singapore Free Press and Mercantile Advertiser, describes what seems to be quite a different dish from the one we are now familiar with:

A familiar dish with the Chinese coolie and Straits school-boy is “laksa”. The vendor of this compound, vermicelli, “rats’ ears” (mush-rooms), and other things in a kind of soup, shouts out every now and then “Laksa a wun!” and many who taste it declare that it is A1.

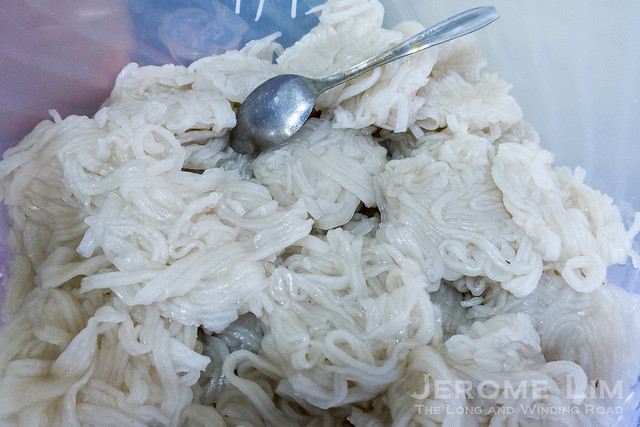

Lakse or laksa, describes these noodles made from sago in Pulau Singkep in the Lingga group of islands in the Riau Archipelago.

One of the many ways in which laksa is served on Pulau Singkep is with a fish broth and sambal.

A poem, penned in 1931 by a prominent personality Mr. Seow Poh Leng – a Municipal Commissioner and a champion of hawkers’ rights – provides an idea of how the dish had by the 1930s, started to evolve. An attempt to draw attention to the difficulties street hawkers faced, the verse also describes how a dough of ground rice became “lumps of tiny snow-white coils” when boiled and which was then “served with tasty gravy and a pinch of fragrant spice”. Published in the Malayan Saturday Post of 16 May 1931, the piece was the writer’s response to the death of a laksa vendor. The vendor had taken his own life after several run ins with the Municipal authorities that deprived him of his livelihood.

Laska Siam, served at another popular Penang laksa stall, this one at Balik Pulau.

By the 1950s, laksa as a dish, seemed to have already taken on several distinct styles. A 1951 article in The Singapore Free Press, “Let’s talk about food”, mentions two types of “Siamese” laksa: one sweet and one hot and sour, along with a “Nonya” laksa. The two variants of “Siamese” laksa are again mentioned in a 1953 Singapore Free Press article on food in Penang. The sour type “Siamese” laksa identified is perhaps the predecessor to the Penang or asam (or assam) laksa dish of today as another 1951 report, this time in The Straits Times on Penang, seems to confirm. The article draws attention to one of Penang’s attractions, Ayer Itam (now spelled Air Itam), to which the young and old would walk six miles or brave a ride on a crowded bus to. Ayer Itam, is identified as “the village with the famous Kek Lok Si”, and (a seemingly already popular) “Siamese” laksa (Air Itam is a location many in Penang flock to today for asam laksa).

What we can perhaps surmise from all of this information is that despite its shared name, laksa in its many variations are really different dishes. Built on an otherwise tasteless base of rice or sago vermicelli or a noodle substitute, how its various forms of laksa have been flavoured to excite the palate, says much about the invention and the creativity of the region’s pioneering food vendors.

Lakse Goreng topped with crushed ikan bilis from Pulau Singkep.

A livelihood to seek in this far-famed town.

My parents they are old but still must toil each day

My father selling bean-curds, my mother selling “kway”.

We left our home and kin to this far distant shore;

And promised to return to see them all once more,

To share with them and theirs what little we have made

By dint of patient toil, by means of honest trade.

The ‘laksa’ I’m preparing that people may be fed

I grind some rice to powder and knead it to a dough

Then press it through a sieve to a boiling pot below.

This stringy mass of flour which hardens as it boils

Is made up into lumps of tiny snow-white coils;

Then served with tasty gravy and a pinch of fragrant spice

My ‘laksa’ finds more favour than the ordinary rice.

Are placed my tooth-some wares and the necessary gears.

In a gourd-shaped earthen vessel the ‘laksa’ simmers low,

All day aboiling gently on charcoal burning slow.

From street to street I wander, my pace a steady trot,

And bear my loaded basket as well as the steaming pot.

The noon day trade I seek and may with luck—oh rare !

Avoid the stern police who ask a certain share.

And more than do their duty unless I pay a ” fee.”

They see that I comply with what the by-laws state;

That is, whatever happens, I must itinerate.

Sometimes from sheer fatigue I pause some breath to take,

To dry my streaming sweat, to ease the limbs that ache;

And then the “Mata-mata” finds me resting there,

And forthwith to the Court I must with him repair.

The fine imposed on me was more than I could pay.

What use is there for me this arduous life to lead?

My humble cries for mercy receive but scanty heed.

By ceaseless toil I tried an honest life to lead.

If I the “tips” forget, the traffic I impede.

And for such bogus crime there is no other way –

Before the Court I’m brought and straightway made to pay.

Yet I would quit right gladly for any work at all,

Seek work at any distance – if only work there be

Without the constant harass and the unofficial fee.

A rickshaw puller – aye the “totee’s” job I’ll do.

I’ll go to Malacca, I’ll go to Trengganu.

Alack! my quest is vain, my faintest hope is gone;

My limbs they are weary, my heart with sorrow torn.

Good-bye to all M.C.’s, good-bye the I.G.P.!

You wish me back to China, you want me off the street;

Posterity shall know I die your wish to meet!

Not satisfied with fines the Magistrates impose

The dreary prison cell must add to hawkers’ woes.

My goods and property you wish to confiscate?

But here you will not win—the law will come too late!

Think not the step I take a very grievous sin.

Right well I am aware of honour due to you;

And thank you from my heart for lessons wise and true.

To comfort your old age my level best I’ve tried.

My efforts seem in vain, the cruel fates decide.

I cannot stoop to crime and slur the family name,

So drink this portion dark, preferring death to shame.

A Malay laksa vendor in Penang, c. 1930s (http://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline | Mrs J A Bennett Collection/National Archives of Singapore).

Gary Stevens on Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Wally Gobetz on Flickr (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0).