I love old university towns and I got to have a look at one of Spain’s oldest, Alcalá de Henares, quite recently. The university established there had its origins in 1293 as Estudio de Escuelas Generales de Alcalá and became the University of Compultense (Universitas Complutensis) in 1499 through the vision of a important church figure at the time as Spain was entering into its Golden Age, a move that was to transform the former college to one of Spain’s most important seats of learning and also lead to the expansion of Alcalá into a planned university town. Although the university has since been moved to Madrid, the city of Alcalá de Henares’ still retains much of the flavour of the old university town and has seen a revival of the old university as the University of Alcalá in more recent times.

A courtyard inside the historic Colegio de San Ildefonso of the University of University of Alcalá.

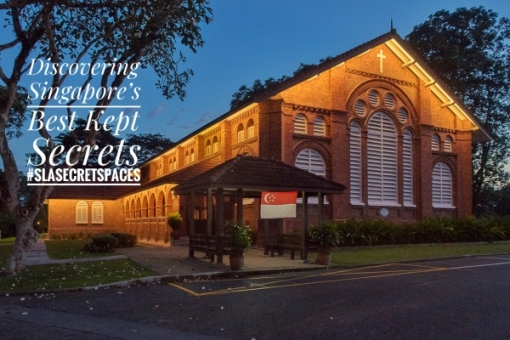

I arrived in Alcalá de Henares in the quiet of a Saturday morning and the first glimpse I had of the city was of its quiet, neat and ordered streets lined with brick and sandstone buildings coloured gold by the light of the morning sun. Alcalá, some 30 kilometres from Madrid, seemed distant enough to be isolated from the hustle and bustle of Spain’s capital city; the dignified air of calm unsurprising perhaps of a city that was reinvented as a seat of learning.

There is much more than meets the eye in Alcalá de Henares.

A street in Alcalá de Henares.

What does surprise in Alcalá is that perhaps there is much more of it than its early weekend demeanour does suggest, the city’s glitter is one that glows not just due to to golden light of the morning, but the that of the city’s fascinatingly storied past. The city’s rich history, which has been recognised by the listing of its historic and university precincts have been listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site since 1998, goes back well beyond the university or even the Moorish origins of its name, Alcalá – derived from the Arabic Al-Qal’at or fortress. This I was to very quickly realise two hours into my stay in the city.

The quiet streets of the university precinct on a Saturday morning.

My visit to Alcalá de Henares was the first stop in what was to turn out to be an amazing journey that also included visits to four other UNESCO World Heritage cities close to Madrid. The trip was made possible by the Spanish World Heritage Cities Group (Ciudades Patrimonio de la Humanidad de España), the Spanish Tourism Board and Thai Airways. Alcalá de Henares, located close to Madrid’s Barajas airport, made it a very convenient first stop.

City Hall as seen from Plaza de Cervantes.

Another view of the university precinct.

One of the things that becomes very quickly apparent about Alcalá, is its association with Spain’s most celebrated literary figure, Miguel de Cervantes; Cervantes’ work, Don Quixote, an icon of a masterpiece that is considered to be one of the most important works in Spanish literature. Alcalá is where the famous writer came into the world during the days of the Spanish Golden Age and Alcalá’s heyday in 1547, and in Alcalá, we find all things Cervantes, including in and around the city’s main square that is very predictably named after him.

The statue of Cervantes in the centre of Plaza de Cervantes.

The main square, Plaza de Cervantes, is where the medieval town of Alcalá and the post-medieval university town meet. The formerly walled medieval town in which there was a Arab, Jewish and Chirstian quarter, lies to the east of the square. To the west is the university town and its ordered streets. In the centre of the square, the centre perhaps of Cervantes’ Alcalá, is where the writer is immortalised in a statue that stands high over the square, holding a quill in his hand.

The northern half of Plaza de Cervantes.

Plaza de Cervantes by night.

It was to the square that I headed out to almost as soon as I put my bags down at the hotel, resisting the urge to climb into the very inviting king sized bed in the beautifully furnished room of the hotel. This despite the lack of sleep having stepped off only hours before from the 12 hour intercontinental flight.

The rooms of the parador as seen from the very peaceful roof top garden.

The room in the parador.

The hotel, Alcalá de Henares’ is surprisingly modern as a Parador. Surprising because the limited experiences I have had of staying in a paradors, were of ones in which the tone of the decor of the rooms seemed to match the history of the buildings they would be found in. Paradors, luxury hotels run by the Spanish government, are usually found in historic buildings such as former palaces, castles and monasteries.

The parador in Alcalá.

The cloisters of the former Convento Santo Tomas.

The old and the new parts of the parador.

In the case of the parador in Alcalá, while it is rather interestingly set up in a 17th Century former Dominican monastery, the Convento de Santo Tomás that has also seen use as a military barracks in the 19th century and a prison in more recent times, its transformation into a parador has given it an ultra modern feel. The parador’s beautifully furnished rooms and spa, does make it all that more difficult to want to leave its premises.

Another view of the cloisters – through a second level window.

The roof top garden by night.

At Plaza de Cervantes, the gaze of a Cervantes is towards the the plaza’s north. Following his gaze and turning west is one of the main cobbled streets of the medieval Jewish quarter, the Calle Mayor, along which the house in which Cervantes was born is found. Furnished with furniture from the era, the two-storey house with an inner courtyard typical of old Castille, is now a museum that is a must visit, especially for all interested in Cervantes’ life and work.

Calle Mayor in the medieval quarter.

Another look at Calle Mayor.

The birthplace of Cervantes.

My travel companions in the courtyard of the birthplace of Cervantes.

An exhibit depicting a scene from a puppet play at the birthplace of Cervantes.

Furnishings for a sanitary room from the period.

The dining room.

It was just past Cervantes’ birthplace on the Calle Mayor that a link to pre-Moorish past was to leap out at me to the beat of of a march. Making its way down the street was a religious procession. While being one very typical in the sense of the Iberian traditions as well as one commemorating a post medieval event, the 1568 return of the relics of city’s patron saints, “los Santos Niños”, Saints Justus and Pastor, the procession also tells of Alcalá’s links to Roman times. The saints, both children, had been martyred for their faith in the year 304 AD, at a time when a Roman settlement, Complutum, was established there.

The statues of los Santos Niños being led through the streets of the medieval quarter.

Figures seen during the procession.

Don Quixote meets the procession along Calle Mayor.

Plaza de Cervantes being at the divide of the old and new Alcalá, is always a good place to start with orientating oneself with Alcalá, especially when one gets to do so high above it with an ascent of 109 steps to the top of the tower of Santa María (Torre de Santa María). Located at the square’s southern edge, the 15th century tower that was the bell tower of the Church of Santa María la Mayor, is one of the few parts of the church that escaped destruction during Spanish Civil War. The view it provides, besides that of a close-up of the storks that seem to be nesting and roosting on top of just about every red rooftop and the spire in the city, is unparalleled and provides a sense of how the city had evolved.

Torre de Santa Maria.

Nesting storks perched on a spire.

A stork in flight.

A view south from the tower.

The view north across Plaza de Cervantes. The medieval quarter is to the left of the square and the university precinct to the right.

Lying in the shadows of the tower, are some of what has survived of the ruined church. One of the attractions the ruins contain is a reproduction of its destroyed baptismal font with pieces of the original font embedded into it. The original font was the one that featured in Cervantes’ baptism in October 1547 and its recreation can now found in the surviving El Oidor chapel. The chapel along with the Antezana chapel are where an Interpretation Centre for the Universes of Cervantes (Los Universos de Cervantes) is now housed. What is also interesting is that the archway that leads to the El Oidor chapel is beautifully decorated with a 16th century grille and beautifully executed Mudéjar plasterwork.

Inside the El Oidor chapel.

The 16th century grille and the arch decorated with Mudéjar plasterwork at the entrance to the El Oidor chapel.

A piece of the original font that is embedded into the reproduction.

Besides the ruins, there are also several other interesting historical structures around the square. One I was able to visit is in the south-eastern corner close to the tower, a two-storey Castilian courtyard building from the 16th century that served as a guesthouse or hostel for university students. The house’s structure has been well preserved along with the courtyard and its laundry well. Used by the municipality in more recent times, two rooms on the upper floor of the building have now been reoccupied by the university.

The courtyard of the hostel.

The laundry well.

A structure of significance lies on the western side of the square. This, the Corral de Comedias, constructed as an open air or courtyard theatre or corral de comedias in 1601, is the oldest in the country to have survived and also one of the oldest theatres still in use in Europe.

Inside the Corral de Comedias.

The stage and the space below the stage, which includes a well.

Modelled after Spain’s first purpose built theatre, the Corral de la Cruz, Alcalá’s corral was originally laid out as all early purpose built theatres in Spain were, replicating the layout and arrangement found in the makeshift theatres that preceded them. The makeshift theatres utilised courtyards of inns and houses and had a stage placed at one end and as with the makeshift arrangements, the purpose-built ones that were a natural progression also featured balconies and boxes on the upper levels of the three free sides, where the audience, segregated according to social status and gender, could watch the performance from.

Stage machinery.

Over time, the Corral de Comedias underwent several transfromations, including the addition of the horseshoe shaped theatrical seating facing the stage in 1831. From 1945 to 1971, the theatre saw use as a cinema, after which it was abandoned. It wasn’t until the 1980s that a massive effort was made to restore it, which was completed only in 2003 when the grand dame’s dignity was restored through its use as a theatre.

The restoration has uncovered some of the original foundations.

As well as provided an idea of the width of the original theatre boxes.

One of the surprising things I learnt about Alcalá, was that it was here that the seeds of the Spanish sponsored adventure led by Christopher Columbus into the new world was planted. The city, serving as the location of the first meeting of the Venetian with Queen Isabella and where the expedition was planned, the events taking place in and around the very majestic Archbishop’s palace tucked away in an area of the city northwest of the main square.

A statue of Isabella by the Archbishop’s Palace.

The palace is especially interesting in that it was built as a residence for the Archbishop of Toledo, the highest ranking member of the clergy in the Catholic church in Spain and through much of Castille’s and Spain’s history, one of the country’s most influential positions, in 1209. Its architecture bears the influences of its long history and within its walls resided not just powerful church men, bit also served as the residence of kings and queens, including Ferdinand and Isabella and in which their daughter Catherine of Aragon, the future first wife of Henry VIII and the Queen of England, was born in 1485. It the annulment of marriage to Catherine that Henry’ sought that was to lead to the split of the English Church from Papal authority in the 1530s.

The Archbishop’s Palace, built in 1209 as the residence of the Archbishop of Toledo.

The Church, or rather an important member of its leadership, was to have a significant influence on the revival of the city’s fortunes, which fell into decline following the expulsion of the Jews in 1496. Cardinal Cisneros, Queen Isabella’s one time confessor and a powerful member of the clergy, established a university in 1499 that was to become one of Spain’s most important seats of learning. The buildings of the university, which would be centered around the magnificent edifice of the Colegio de San Ildefonso put up by Cisneros east of the medieval town, to which I will devote more detail to in a separate post, has to be one of the highlights of a visit to Alcalá.

The Colegio de San Ildefonso built by Cardinal Cisneros.

A visit to Alcalá, as in the rest of Spain, would of course, not be complete without indulging in its gastronomic offerings. There is a mix of old and new, traditional and fusion that can be found along the city’s streets. The parador for one, offers two restaurants, in which a full meal can be savoured for a reasonable outlay and is great value for money. One is in the more traditional setting of the Restaurante Hostería del Estudiante across the street from the main lobby of the parador at the former Colegio Menor de San Jerónimo. The other in a more contemporary setting of the Restaurante de Santo Tomás set in the cloisters of the former Convento de Santo Tomás.

The traditional setting of the Restaurante Hostería del Estudiante.

There is also the chance to savour the more modern interpretations of traditional dishes in more contemporary settings in Alcalá, with restaurants such Plademunt in the quiet streets of the new part of the city and Ambigú in the historic quarter, just by the Teatro Salón Cervantes. Both restaurants are helmed by young culinary talents. On offer at Plademunt are the extraordinary tapas creations of Ivan Plademunt that feature some very traditional and hearty working class comfort foods from the region such as migas and atascaburras as well as pinchos of pintxos from the Basque country.

Plademunt.

Migas, a traditional dish made from a base of breadcrumbs.

Ivan Plademunt demonstrating how Atascaburras is made.

Pinchos.

The Teatro Salón Cervantes on Calle Cervantes.

Ambigú’s offerings include many favourites including grilled octopus, sardines and a dessert to die for, torrija. The utterly sinful dessert, traditionally served during Lent and the Holy Week, is made from a base of bread soaked in milk and is similar to the English bread and butter pudding, only better!

Offerings at Ambigú include the utterly sinful torrija.

It was a pity lunch at Ambigú can on the back of a visit to Esencias Del Gourmet on Calle Mayor just around Cervantes’s birthplace . The proprietor of Esencias Del Gourmet holds a fun yet enlightening food and wine appreciation experience, which was to provide me not only with a much better appreciation of wine and how fine foods can complement wine and bring out its flavours, but also a full stomach that left me with little room for much more.

Esencias Del Gourmet on Calle Mayor.

Wine appreciation experience at Esencias del Gourmet.

Unseen Alcalá – the former women’s prison behind the parador.

The entrance to the former women’s prison after dark.