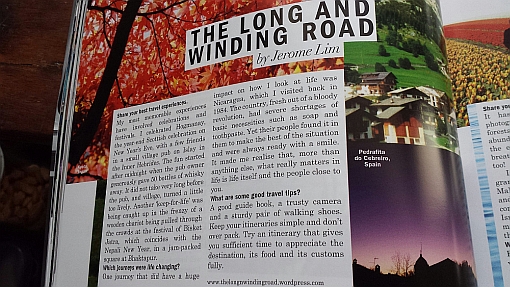

In today’s age of air travel, it would probably be difficult for many of us to want to embark on a journey between continents that might have taken weeks, or even a journey between cities in the region taking at least a few days, other than when one is perhaps considering going on a leisurely cruise. There was a time however, when such a journey would have had to be made out of necessity and not to indulge oneself in leisure as we would be inclined to these day. It was perhaps in the 1970s when air travel became accessible (and affordable) to many, and up to that point, travel between the regional ports would have probably been made aboard a cargo liner on which passengers were allowed to be carried on.

The M.V. Kimanis and several other cargo liners owned by the Straits Steamship Company plied the route between Borneo and the Malayan Peninsula (Source: W.A. Laxon, The Straits Steamship Fleets).

This was a time when just the thought of a voyage by sea might have evoked the romantic notion of travelling in style and luxury that is associated with the ocean liners of the North Atlantic. Indeed, for the well heeled, the leisurely journey might have been taken in lavishly decorated cabins, whilst being waited on by a steward dressed in all whites, in a setting, as I was told, could be compared to one in a Joseph Conrad novel. For the less well off, there would have been a choice of a more modest second class cabin which would have been comfortable enough for the journey; or, in a less than comfortable third class dormitory like cabin (if there were any – many of the ships coming from India had this), or perhaps as a deck passenger. A passage as a deck passenger would be unheard of these days, especially with the adoption of the International Ship and Port Security (ISPS) Code – one of a slew of measures implemented in the wake of the 9-11 attacks. Back then, it would have been a cheap and practical means of getting about, with deck passengers having to brave the elements during the passage on the open deck or perhaps, where the situation might have allowed it, in the cargo holds.

The M.V. Kimanis was a 90 metre long, 3189 ton, cargo liner built in Dundee in 1951 and was in the Straits Steamship fleet up to 1982.

One of the local shipping companies that ran a passenger service was the now defunct Straits Steamship Company. The Singapore based company was founded in 1890 and at its height, operated a fleet of 53 vessels, plying routes that connected ports in the Malayan peninsula, including Singapore with ports in the far flung corners of British Borneo. Many of the ports in Borneo would have had names steeped in the history of the rule of the British and the White Rajahs (in Sarawak), such as Jesselton (now Kota Kinabalu). Many of the ships that the company operated had themselves been named after the ports which the company served.

A subsidiary of Straits Steamship Company started Malayan Airways, which later became MSA and was split into two entities, Singapore Airlines and Malaysian Airline System.

By the time the 1970s had arrived, air travel had taken root and demand for passenger travel by sea had diminished (incidentally, it was a subsidiary of the Straits Steamship Company, that started Malayan Airways, the predecessor to Malaysia-Singapore Airlines (MSA), from which both Malaysian Airline System (MAS) and Singapore Airlines (SIA) were born). The Straits Steamship Company thus promoted passenger travel on the ships they operated for leisure (as a cheaper alternative to the one offered on the M.V. Rasa Sayang which was then offering cruises on the Malacca Straits and around the Indonesian Islands before being sold off a year or so after a tragic fire killed a few crew members in 1977), offering a window into a world of a forgotten age of sea travel. The cost of was a very affordable $80 for the three day return trip to Port Swettenham (or Port Klang as the port had just been renamed as), and it was on such a voyage, aboard one of the Straits Steamship’s vessels, the M.V. Kimanis, that I had an opportunity to have that experience, not once, but twice in 1975.

On the main deck of the Kimanis.

The first voyage that I had on the Kimanis would best be described as an adventure of a lifetime. It had been my very first experience on board a ship and one in which provided me with a view, not just into what life was on board, but also a first hand experience of the stories that I had heard of a voyage on what seemed to me, the “high seas”. It was a voyage that began one evening from Clifford Pier, and via a launch that took us out from the Inner Roads to the Outer Roads and the Eastern Anchorage, where the M.V. Kimanis was anchored. Arriving at the accommodation ladder of the davit rigged black vessel, which featured three white deckhouses, it was with some difficulty that we got onto the ladder having to contend with the violent rolling and heaving of the launch, needing the assistance of the receiving crew members of the Kimanis. I still remember being quite afraid of falling in – even as I was ascending the ladder to the main deck of the vessel.

Wandering around the main deck of the Kimanis was an adventure in itself.

Once onboard, we were greeted by the Chief Steward, a Hainanese man with a greying head of hair, decked in a starched white shirt with epaulettes that seemed to extend up from his shoulders, and brought to our cabins by a steward. The second class cabins we were to stay in were on the next deck above, located along the ship’s side, and had tiny portholes from which we could have a view of the numerous ships that lay at anchor. The cabins were modestly furnished, two single bunks, a rattan chair and dresser, a wardrobe and a wash basin. Showers were to be taken and visits to the toilet were to be made in the communal washrooms arranged on the centreline at the aft end of the alleyway. A door at this end on the aft bulkhead opened to an open deck which also provided access to the main deck below and the deck above. Right at the after end of the next deck was an open deck with an awning that offered partial shelter from the elements on which a bar counter was located, with tables and chairs that formed an open air lounge area. That was where passengers would sit and exchange stories and I remember a man who had started his journey in Tawau with quite a few interesting stories to tell. I can’t remember any of them, but what I do remember very vividly was how he looked – he wore the scars of burns to his face very prominently. We had also on that voyage, met a very friendly and talkative Australian man, from whom I had first heard of what we call the papaya being referred to as a “paw-paw”. He also introduced to a gourd to us which he said was delicious, which he referred to as a choko – which we would later discover was also planted in the Cameron Highlands.

The bar area where passengers exchanged stories.

Besides lounging around at the bar, the day long voyage to Port Klang provided an opportunity for my sister and me to roam the main deck – I was fascinated by the vents that seemed to rise like trumpets out onto the main deck. Somehow, I had imagined them to be sound pipes through which the men working below decks could communicate with crew on the main deck. Meal times were particularly interesting and a steward would alert passengers to meal times by walking through the accommodation area ringing a bell, which would trigger a procession of children following the steward around as if he was the Pied Piper of Hamelin. Meals were served very formally and besides having to dress appropriately for meals, we had to pay careful attention to table etiquette. That was also the first occasion in which I was to be confronted by the intimidating array of cutlery on the table. I quickly learnt the trick for navigating through the cutlery, starting from the outside in as each course was served.

Meal times were particularly interesting on board the Kimanis. A typical menu (Source: W.A. Laxon, The Straits Steamship Fleets).

Arriving at Port Klang, we were greeted by the sight of the wharf side container cranes, which I imagined to be chairs of giants, half expecting to meet a giant on the passage into port. Tugs boats appeared as the ship was guided into port, and went alongside, as I looked forward in anticipation of being able to go ashore. It was on this particular trip that we first visited Genting Highlands, taking a bus into Kuala Lumpur where we could catch a taxi to Genting. I remembered the journey down quite well for the way the taxi driver negotiated the hairpin bends at a seemingly high speed, and as a result, my mother swore never to take a taxi to Genting again! The stay in Port Klang which had been scheduled for one day, spilled over into a second day. We were told that there was always a slowdown for one reason or another at the port – and so we were to have a four day stay on board for the price of three days!

Up on the Bridge - the children on board were given a treat by the Scottish Captain who allowed each of us to handle the helm for about a minute or so.

Little did I know it then, it was on the return voyage to Singapore that the children on board were in for a treat. The ship’s Captain, a Scotsman, invited us children up to view the Bridge, and provided each of us with the chance to be at the helm where we could have a hand in steering the ship. While this experience lasted maybe only for a minute or so, it was certainly a big treat leaving a big impression on me, and at that moment, I decided that I did not want to be a pilot that I seemed to always have wanted to be, and instead thought that it would be more my cup of tea to sail the seven seas and see the world at the same time. I was to have a second experience on the Kimanis later that same year, one which perhaps, I would devote another post to. However, it was this first experience that was to be the one that I would most remember.