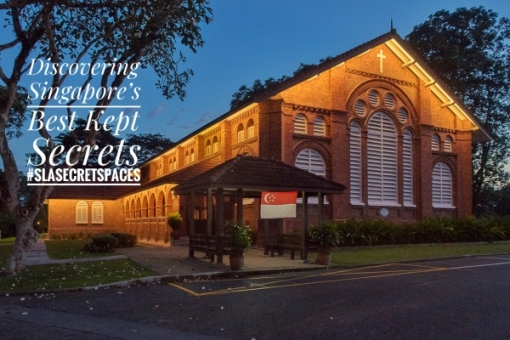

The process of acquainting myself with the shores of Singapore for a project I am working on, Points of Departure, has provided me with some incredible experiences. One that I was especially grateful to have had was the experience of paddling through a green watery space that is almost magical in its beauty. Set in the relatively unspoilt lower reaches of Sungei Khatib Bongsu, one of Singapore’s last un-dammed rivers, the space is one that seems far out of place in the Singapore of today and holds in and around its many estuarine channels, one of the largest concentration of mangroves east of the Causeway along the island’s northern coast.

Paddling through the watery forest at Sungei Khatib Bongsu.

The much misunderstood mangrove forest, is very much a part of Singapore’s natural heritage. The watery forests, had for long, dominated much of Singapore’s coastal and estuarine areas, accounting for as much as an estimated 13% of Singapore’s land area at the time of the arrival of the British. Much has since been lost through development and reclamation and today, the area mangrove forests occupy amount to less that 1% of Singapore’s expanded land area. It is in such forests that we find a rich diversity of plant and animal life. Mangroves, importantly, also serve as nurseries for aquatic life as well as act as natural barriers that help protect our shorelines from erosion.

Khatib Bongsu is a watery but very green world.

The island’s northern coast was especially rich in mangrove forests. Much has however, been cleared through the course of the 19th and 20th centuries, with large tracts being lost during the construction of the airbase at Seletar and the naval base at Sembawang in the early 1900s. The mangroves of the north, spread along the coast as well as inland through its many estuaries, along with those found across the strait in Johor, were once the domain of the Orang Seletar. A nomadic group of boat dwellers, the Orang Seletar had for long, featured in the Johor or Tebrau Strait, living off the sea and the mangroves; finding safe harbour in bad weather within the relatively sheltered mangrove lined estuaries.

Mangrove forests had once dominated much of coastal Singapore.

Boat dwelling Orang Seletar families could apparently be found along Singapore’s northern coast until as recently as the 1970s. While the Orang Seletar in Singapore have, over the course of time, largely been assimilated into the wider Malay community, the are still communities of Orang Seletar across the strait in Johor. Clinging on to their Orang Seletar identity, the nine communities there live no longer on the water, but on the land in houses close to the water.

Safe harbour in the watery woods.

It is the labyrinth of tree shaded channels and the remnants of its more recent prawn farming past that makes the side of the right bank of Sungei Khatib Bongsu’s lower reaches an especially interesting area to kayak through. Much has since been reclaimed by the mangrove forest and although there still is evidence of human activity in the area, it is a wonderfully green and peaceful space that brings much joy to to the rower.

The canalised upper part of Sungei Khatib Bongsu.

The area around Sungei Khatib Bongsu today, as seen on Google Maps.

Paddling through the network of channels and bund encircled former prawn ponds – accessible through the concrete channels that once were their sluice gates, the sounds that are heard are mostly of the mangrove’s many avian residents. It was however the shrill call of one of the mangrove’s more diminutive winged creatures, the Ashy Tailorbird, that seemed to dominate, a call that could in the not too distant future, be drowned out by the noise of the fast advancing human world. It is just north of Yishun Avenue 6, where the frontier seems now to be, that we see a wide barren patch. The patch is one cleared of its greenery so that a major road – an extension of Admiralty Road East, can be built; a sign that time may soon be called on an oasis that for long has been a sanctuary for a rich and diverse avian population.

The walk into the mangroves.

The beginnings of a new road.

The Sungei Khatib Bongsu mangroves, lies in an area between Sungei Khatib Bongsu and the left bank of Sungei Seletar at its mouth that lies beyond the Lower Seletar Dam that has been designated as South Simpang; at the southern area of a large plot of land reserved for public housing that will become the future Simpang New Town. The area is one that is especially rich in bird life, attracting a mix of resident and migratory species and was a major breeding site for Black-crowned Night Herons, a herony that has fallen victim to mosquito fogging. While there is little to suggest that the herons will return to breed, the area is still one where many rare and endangered species of birds continue to be sighted and while kayaking through, what possibly was a critically endangered Great-billed Heron made a graceful appearance.

Evidence of the former prawn ponds.

Kayaking into the former ponds.

It is for the area’s rich biodiversity that the Nature Society (Singapore) or NSS has long campaigned for its preservation and a proposal for its conservation was submitted by the NSS as far back as in 1993. This did seem to have some initial success and the area, now used as a military training area into which access is largely restricted, was identified as a nature area for conservation, as was reflected in the first issue of the Singapore Green Plan. Its protection as a nature area seemed once again confirmed by the then Acting Minister for National Development, Mr Lim Hng Kiang, during the budget debate on 18 March 1994 (see: Singapore Parliament Reports), with the Minister saying: “We have acceded to their (NSS) request in priorities and we have conserved Sungei Buloh Bird Sanctuary and Khatib Bongsu“.

Unfortunately, the area has failed to make a reappearance in subsequently releases of the list of nature area for conservation, an omission that was also seen in subsequent editions of the Singapore Green Plan. What we now see consistently reflected in the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) Master Plans (see: Master Plan), is that as part of a larger reserve area for the future Simpang, the area’s shoreline stands to be altered by the reclamation of land. Along with land reclamation, plans the Public Utilities Board (PUB) appears to have for Sungei Khatib Bongsu’s conversion into a reservoir that will also include the neighbouring Sungei Simpang under Phase 2 of the Seletar-Serangoon Scheme (SRSS), does mean that the future of the mangroves is rather uncertain.

A resident that faces an uncertain future.

Phase 2 of the SRSS involves the impounding of Sungei Khatib Bongsu, Sungei Simpang and Sungei Seletar to create the Coastal Seletar Reservoir. Based on the 2008 State of the Environment Report, this was to be carried out in tandem with land reclamation along the Simpang and Sembawang coast. The reclamation could commence as early as next year, 2015 (see State of the Environment 2008 Report Chapter 3: Water).

In the meantime, the NSS does continue with its efforts to bring to the attention of the various agencies involved in urban planning of the importance of the survival of the mangroves at Khatib Bongsu. Providing feedback to the URA on its Draft Master Plan in 2013 (see Feedback on the Updated URA Master Plan, November 2013), the NSS highlights the following:

Present here is the endangered mangrove tree species, Lumnitzera racemosa, listed in the Singapore Red Data Book (RDB). Growing plentifully by the edge and on the mangrove is the Hoya diversifolia. On the whole the mangrove here is extensive and healthy, with thicker stretches along Sg Khatib Bongsu and the estuary of Sg Seletar.

A total of 185 species of birds, resident and migratory, have been recorded at the Khatib Bongsu area. This comes to 49 % of the total number of bird species in Singapore (376, Pocket Checklist 2011, unpublished ) – almost comparable to that at Sungei Buloh Wetland Reserve. 13 bird species found here are listed in the RDB and among these are: Rusty-breasted Cuckoo, Straw-headed Bulbul, Ruddy Kingfisher, Grey-headed Fish Eagle, Changeable Hawk Eagle, White-chested Babbler, etc. The Grey-headed Fish Eagle and the Changeable Hawk eagle are nesting in the Albizia woodlands in this area.

The mangrove dependent species present are : Crab-eating Frog, Dog-faced Water Snake & Malaysian Wood Rat. The Malaysian Wood Rat is regarded is locally uncommon. In 2000, Banded Krait (RDB species) was found here near the edge mangrove. Otters, probably the Smooth Otter, have been sighted by fishermen and birdwatchers in the abandoned fish ponds and the Khatib Bongsu river.

URA Master Plan 2014, showing the reserve area at Simpang.

It will certainly be a great loss to Singapore should the PUB and the Housing and Development Board (HDB) proceed with their plans for the area. What we stand to lose is not just another regenerated green patch, but a part of our natural heritage that as a habitat for the diverse array of plant and animals many of which are at risk of disappearing altogether from our shores, is one that can never be replaced.

The present shoreline at Simpang, threatened by possible future land reclamation.

The white sands at Tanjong Irau, another shoreline under threat of the possible future Simpang-Sembawang land reclamation.