Street names, especially ones in common use, often tell an interesting tale. Such is the case with Middle Road. Constructed late in the first decade that followed British Singapore’s 1819 founding by Sir Stamford Raffles, parts of Middle Road have become known by a mix of names in the various vernaculars. Each provide a glimpse into the streets fascinating past, the communities it played host to and the trades and institutions that marked it. It is its official name, Middle Road, that seems to have less to reveal and what Middle Road the middle, is a question that has not been quite as adequately answered.

Often the resource of choice in seeking a better understanding of a Singapore street name and its origins is the book ‘Singapore Street Names: A Study of Toponymics’, authored by Victor Savage and Brenda Yeoh. The book however, does not quite provide the answer to the question of what made Middle Road the middle in explaining that the street was (or may have been) a line of demarcation between the trading post’s European Town and a designated ‘native’ settlement to its east. Reference has to be made to the 1822 Town Plan, for which Raffles’ provided a specific set of instructions, in the allocation of areas of settlement along ethnic lines with the civic and mercantile districts at the town’s centre. A set of written instructions was also provided by Raffles to members of the Town Committee. Based on the plan and the written instructions, the European Town was to have extended eastwards from the cantonment for “as far generally as the Sultan’s (settlement)”, with an ‘Arab Campong’ in between. This meant that the line demarcating the two districts was not Middle Road, but would have been Rochor Road or a parallel line to its northeast.

There is an older attempt to explain what the ‘middle’ in Middle Road might have been. This was made in 1886 by T J Keaughran, a one-time employee of the Government printing office and resident of Singapore in the late 1800s. In a Straits Times article, ‘Picturesque and busy Singapore’, Keaughran described Middle Road as being “perhaps more appropriately, the central division or section of the city”. There may be some merit in this suggestion based on the 1822 Town Plan. What seems however to be more obvious is that Middle Road ran right down the middle of the European quarter. Middle Road was also, quite literally, the middle road of three parallel roads running northwest to southeast through the European Town.

It would appear that the European Town, or at least the section that was allocated to it, never quite developed as Raffles had envisaged. Middle Road would turn out to be the centre of many communities, none of which was quite European. Hints of European influences do however exist in the Portuguese Church and in the former St Anthony’s Convent. The Portuguese Church — as it was once commonly referred to, or St Joseph’s Church, long a focal point of Singapore’s Portuguese Eurasian community, traces it roots to the Portuguese Mission’s Father Francisco da Silva Pinto e Maia, a one time Rector of St Joseph’s Seminary in Macau and owes much to the generosity of Portuguese physician turned settler, merchant and plantation owner, Dr Jose D’Almeida. It was in D’Almeida’s exclusive beach front house in the area that Liang Seah Street is today, that the mission’s first masses were held in 1825 – a year in which both Father Maia and Dr D’Almeida set foot on a permanent basis in Singapore.

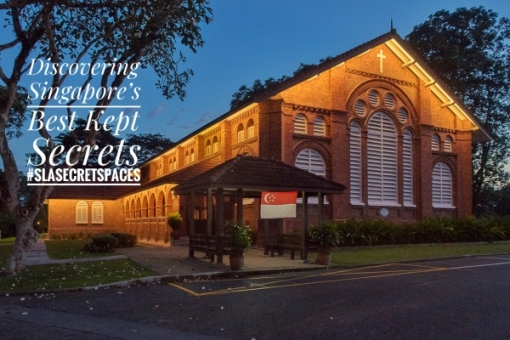

The land on which the Beach Road house stood, had been procured by Dr D’Almeida during a stopover whilst on a voyage to Macau in 1819 with the help of Francis James Bernard, acting Master Attendant, son-in-law of Singapore’s first resident William Farquhar, and perhaps more famously, the great, great, great, great grandfather of Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau. D’Almeida also had a house built on the plot, which Bernard occupied whilst the physician was based in Macau. Political events in Portugal, and its delayed spread to Macau, would bring both Father Maia and D’Almeida to Singapore via Calcutta. D’Almeida’s Beach Road house was used to celebrate masses until 1833. A permanent church building for the Church of São José (St Joseph) would eventually be established at the corner of Victoria Street and Middle Road in the mid-1800s. What stands on the site today is a 1912 rebuild of this church. Initially administered by the Diocese of Goa and later, by the Diocese of Macau, the church’s links with Portugal were only broken in 1981, although parish priest appointments continued to be made by the Diocese of Macau until 1999 when Macau reverted to Chinese rule and the Portuguese Mission was dissolved. The church has since 1981, come under the jurisdiction of the Catholic Archdiocese of Singapore.

The Portuguese Mission would also establish St Anna’s School in 1879. The school for children of poor parishioners, is the predecessor to St Anthony’s Boys’ School (now St Anthony’s Primary School) and St Anthony’s Convent (now St. Anthony’s Canossian Primary School). A spilt into a boys’ and a girls’ school in 1893 saw the two sections going their separate ways. The setting up of the girls’ school would see to an Italian flavour being added to Middle Road, when four nuns of the Italian-based Canossian order came over from Macau in 1894 to run the girls’ section. Two of the nuns were Italian and another two Portuguese and in the course of its time in Middle Road, many more nuns of Italian origin would arrive. Those who were boarders or schoolgirls from the old convent days in Middle Road will remember how old-fashioned methods of discipline that the nuns brought with them were administered in heavily accented English with a certain degree of fondness.

While the convent may have moved in 1995, the buildings that were put up over the course of the 20th century along Middle Road to serve it are still there and stands as a reminder of the work of the Canossian nuns. Now occupied by the National Design Centre, its former chapel building is also where the legacy of another Italian, Cav Rodolfo Nolli has quite literally been cast in stone. In the former convent’s chapel, now the centre’s auditorium, watchful angels in the form of cast stone reliefs made by Nolli — Nolli’s angels as I refer to them — count among the the last works that the sculptor executed here before his retirement. The angels have watched over the nuns, boarders, orphans and schoolgirls since the early 1950s and are among several lasting reminders of Cav Nolli. The Italian craftsman spent a good part of his life in Singapore, having first arrived from Bangkok in 1921. Except for a period of internment in Australia during the Second World War, Nolli was based in Singapore until 1956. His best known work in Singapore is the magnificent set of sculptures, the Allegory of Justice, found in the tympanum of the Old Supreme Court.

Among the common names associated with Middle Road is a now a rather obscure one in the Hokkien vernacular, 小坡红毛打铁 (Sio Po Ang Mo Pah Thi). This is another that could be thought of as providing a hint of another of the street’s possible ‘ang mo’ (红毛) or European connections. The Sio Po (小坡) in the name is a reference to the ‘lesser town’ or the secondary Chinese settlement that developed on the north side of the Singapore River (as opposed to 大坡 tua po — the ‘greater town’ or Chinatown). A literal translation of Pah Thi (打铁) would be “hit iron” — a reference to an iron-working establishment, which in this case was the J M Cazalas et Fils’ (J M Cazalas and Sons’) iron and brass foundry. Established in 1856 by Mauritius born Frenchman Jean-Marie Cazalas, the foundary occupied an area bounded by Middle Road, Victoria Street, the since expunged Holloway Lane, and North Bridge Road, a site on which part of the National Library now stands.

The business survived in one form or another in the area right up to 1920. J M’s son, Joseph, who inherited the business, renamed it Cazalas and Fils. In 1887, Chop Bun Hup Guan bought the foundry over and had it renamed Victoria Engine Works. The last name that the business was known by was Central Engine Works, a name it acquired when it again changed hands in the 1900s. Central Engine Works’ move in 1920 to new and “more commodious” premises in Geylang, paved the way for the site’s redevelopment and saw to the removal of all traces of the foundry. The name Central Engine Works would itself fade into oblivion when it became a victim of the poor economic conditions that persisted through much of the 1920s. The firm went into voluntary liquidation in the early 1930s. The Empress Hotel, which opened in 1928, was erected on part of the former foundry’s site and became a landmark in the area. It was known for its restaurant which produced a popular brand of mooncakes, the ‘Queen of the Mooncakes’. Looking tired and worn, the Empress Hotel came down in 1985, when the wave of urban redevelopment swept through the area.

The setting up of the Cazalas foundry up came at a time when the European Town was already on its way to becoming the ‘Lesser Town’. One of the reasons contributing to the change in status of the designated European area and its choice beachfront plots may have been the preference amongst the settlement’s European ‘gentry’ for the more pleasant inland area of the island as places of residence as the interior opened up. Among the larger groups contributing to the influx of non-European settlers in the area were the Hainanese — who could be thought of as ‘latecomers’ to the Chinese Nanyang diaspora. The Hainanese established clan or bang boarding houses in the area and by 1857, a temple dedicated to Mazu was erected at Malabar Street. Middle Road became the Hainanese 海南一街 or Hylam Yet Goi. The area is today still thought of as a spiritual home to the community, who today form the fifth largest of the various Chinese dialect groups in Singapore. The Singapore Hainan Hwee Kuan and the Tin Hou Kong (the since relocated Mazu temple) is also present in the area at Beach Road. The area can also be thought of as the home of the Singapore brand of Hainanese Chicken Rice having been were it was conceived and for many years served by its inventor.

Among other names associated with Middle Road was 中央通り(Chuo Dori), Japanese for ‘Central Street’ and the محلة (Mahallah) — an Arabic term meaning ‘place’ and used by the Sephardic Jewish community who came through Baghdad to describe the Jewish neighbourhood that formed at the end of the 19th century in and around the northwest end of Middle Road. There were also a host of names in Hokkien that refer to Mangkulu 望久鲁 or Bencoolen — a reference to the Kampong Bencoolen, which was established in the area.

One name that includes the name is 望久鲁车馆 or Mangkulu Chia Kuan — the jinrikisha registration station in the area that later became the Registry of Vehicles (where Sunshine Plaza is today. As with the station at Neil Road, a station was established in the Middle Road area due to the proliferation rickshaw coolie kengs or quarters and rickshaw operators in the area, many of which were run by other groups of late arrivals among the Chinese migrants, the Hokchia and the Henghwa. Also mixed into the area around the Lesser Town as the years went by were other migrant communities, who included Hakkas, the people of Sam Kiang (the three ‘kiangs‘ or ‘jiangs‘ — Zhejiang, Jiangsu and Jiangxi) who are sometimes described as Shanghainese, South Indians and Sikhs. The people of Sam Kiang were quite prominent and featured in the furniture making and piano trading businesses, books and publishing, and tailoring — Chiang Yick Ching, who founded CYC Shirts at Selegie Road was an immigrant from Ningbo in Zhejiang as was Chou Sing Chu, the founder of Popular Book Store at North Bridge Road. The Hakkas were involved in the canvas trade, and were opticians and watch dealers. They were also the shoe making and shoe last making factories around Middle Road, which was once a street known for it Chinese shoe shops.