Ravaged by the passage of time and probably neglect, a structure which harks back seemingly to the days of empire and dominion, sits somewhat obscurely and well forgotten on the southern slope of Bukit Purmei in Kampong Bahru. Dominated by the emblems near it of a Singapore that spares little thought for such vestiges of its past, the structure, a walled compound, with an entrance archway suggesting a European origin, hides a world that has much to do with the days of empire that is anything but European.

The well hidden reminder of a past we have long discarded.

The walled compound, referred to in the past as Keramat Bukit Kasita, is well hidden from view. Located on what can probably be described as a short spur on the Bukit Purmei slope, it sits on the edge of a public housing estate, behind a disarray of zinc topped shacks. A narrow path leads through the shacks – home to the guardians of the compound, who perhaps are also the keepers of a past which would otherwise have been discarded; rising up to where the archway is. Beyond the locked gates – a more recent addition to the archway, it is the unmistakeable sight of Malay graves – many have its headstones covered in the yellow cloth that is associated with Malay royalty, that greets the eye. There are also several on which green cloth is wrapped over – green being the colour of Islam.

The concrete jungle Keramat Bukit Kasita now finds itself in. The blocks of flats painted in light blue and white are of Bukit Purmei.

One of the keepers of the tombs, a rather chatty lady who identified herself as “Umi”, tells the group of us standing by the archway that the tombs are those of the Riau-Lingga branch of the Johor Royal family, hence the yellow cloth and the name Tanah Kubor diRaja by which the site is also known as. The earliest grave there she says, is one which dates back to 1721. She also made mention of a “Sultan Iskandar Shah”, buried at the site, about which I was rather puzzled as I was intrigued.

A look into the compound from the back of it.

“Wouldn’t Sultan Iskandar Shah be buried in Melaka” I ask. Umi tells me there might have been more than one “Iskandar Shah”, as names are often recycled down the line.

A Berita Minggu article from Nov 1998 tells us of a notice which identifies the tomb of a “Sultan Iskandar Shah” under in a yellow shed.

Interestingly a Berita Minggu article published on 29 November 1998 also makes mention of “Sultan Iskandar Shah”, drawing reference to a notice put up at the site on which the words “terdapat sebuah makam seorang sultan, Almahurum Sri Sultan Iskandar Shah, di pondok tuning itu“, which translates into “there is a tomb of a sultan, the late Sri Sultan Iskandar Shah, in the yellow shed”.

A zinc topped dwelling, one which hides the walled compound from view.

The article which is written based on an interview the newspaper did with a previous keeper of the tombs, an En. Azmi Saipan, also mentions that this “Sultan Iskandar Shah”, was thought to have died some 400 years previously – placing him in the 16th Century, well after the passing of the Iskandar Shah, the last king of Sang Nila Utama’s Singapura and the founder of Melaka, that we know well from our history texts.

What greets the eye at the bottom of the spur – used as a barber shop until very recently.

There is a suggestion that is offered by a Radin Mas heritage guide which is put together by the Radin Mas Citizens’s Consultative Community, that the burial site was set up in 1530 by Sultan Alaudin Riayat Shah II – who established the Johor Sultanate out of the ruins of the Melaka Sultanate which was deposed through the Portuguese conquest of Melaka in the early 16th Century. Whether or not Sultan Alaudin Riayat Shah II who ruled from 1528 to 1564 could be that “Sultan Iskandar Shah” the keepers speak of isn’t certain, although the association remains a possibility. This does also does date the burial grounds some two hundred years before the “oldest grave” which Umi made a mention of.

The grounds of the former De La Salle School which opened in 1952 are right next to the keramat.

We also learn from Umi that she was from a family of caretakers appointed by a member of the Johor Royal family to take care of the Istana Woodneuk and the grounds of the former Istana Tyersall until some 15 years ago, before being asked by a “Tunku” to move to Bukit Purmei to look after the Bukit Kasita site, which she says is still in the hands of the State of Johor. A check on the Singapore Land Authority’s one map site shows however that Bukit Kasita is within a parcel of land which is owned by the Housing and Development Board – although I am given to understand that it is possible that the site itself could still be owned by the Johor State.

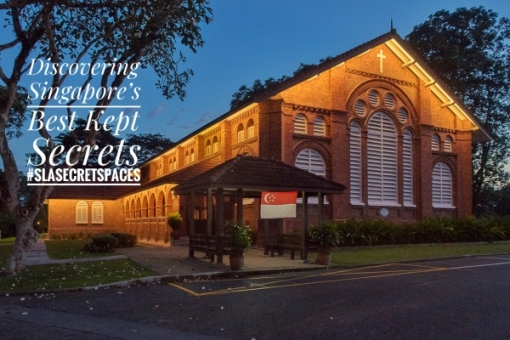

Query on ownership of land on which Keramat Bukit Kasita is on via SLA’s One Map site.

While it is uncertain what origins of the site are, we do know that there is at least the graves of a branch of the Johor Royal line all of which can be traced back to Sang Nila Utama and his successors who ruled Singapura and subsequently the Sultanate of Melaka, is can be found behind the walls. This branch, are the descendants of the rulers of the Riau-Lingga Sultanate which was set up by the Dutch out of the remnants of the Johor-Riau-Lingga Sultanate they controlled through the appointment of the Sultan Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah the younger son of Sultan Mahmud Shah III following his death in 1812 and cemented by the Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824.

The locked gates.

It was Abdul Rahman’s elder half brother, Hussein who was set up by Raffles as Sultan of Johor and Singapore, in Kampong Glam – Hussein’s descendants are buried in another site at the Old Malay Cemetery in Jalan Kubor.

The ‘Tombs of Malayan Princes’ at Jalan Kubor.

The Riau Sultanate was abolished when the Dutch drove an uncooperative Sultan Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah II, the great-great-grandson of Sultan Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah through his great-granddaughter Tengku Fatimah, from his seat in Pulau Penyengat into exile in Singapore in 1911. Sultan Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah II, the very last Sultan of Riau-Lingga, died a poor man in 1930 and along with several of his descendants, is buried at Bukit Kasita. This does make the cluster, one of three connected, albeit distantly, with the Johor Royal family.

Sultan Abdul Rahman Muazzam Shah II, the last sultan of Riau-Lingga who died in exile in Singapore in 1930 (source: www.royalark.net).

The other two are the Tanah Kubor Temenggong at Telok Blangah where the Temenggong with whom Raffles negotiated with in setting up the East India Company’s trading post in Singapore, and from whom the current line of Johor Sultans descended, Temenggong Abdul Rahman is buried; and the Old Malay Cemetery at Kampong Glam, where the “Tombs of Malayan Princes” – many of whom were descendants of Sultan Hussein, is found. Tanah Kubor Temenggong along with the Masjid Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim are on land owned by the State of Johor. The tomb of Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim after whom the mosque is named is also found in that burial site. It was Temmenggong Deang Ibrahim’s son, Abu Bakar, who established the current Johor Sultanate.

Another view of the Tanah Kubor diRaja / Keramat Bukit Kasita.

It is thought that the area where Bukit Kasita is, was where one of the oldest settlements in Singapore was established well before the arrival of Raffles and the resettlement of the Temenggong and his followers by Raffles to the Telok Blangah area. It might have been Abu Bakar as Temenggong who permitted the establishment of a settlement by followers of the ousted last Bendahara of Johor in Pahang Tun Mutahir in 1863, many of whom fled to Singapore and Johor at the end of the Pahang Civil War of 1857 to 1863. Tun Mutahir was defeated by the Bendahara’s younger half brother Tun Ahmad who established the Pahang Sultanate. The settlement came to be known as Kampong Pahang – which is shown in a map of Singapore from 1907, one of several villages of the same name set up by fleeing followers of Tun Mutahir, another of which was on Pulau Tekong.

Detail of a 1907 map of Singapore showing Kampong Pahang at Bukit Purmei / Bukit Kasita.

As to how the Bukit Kasita site came to be venerated as a keramat, a clue is found in a paper published in the Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society in 2003 by P.J. Rivers. Rivers identifies two graves which are venerated as keramats, one is of a Raja Ahmad which Rivers identifies as Keramat Bukit Kasita. The second grave is that of a Raja Tengku Fatimah which is venerated on the basis that the waters of spring next to the tomb which is said to have healing powers.

Another keramat, that of Radin Mas Ayu, just a stone’s throw away on the slopes of Mount Faber.

Outside the gate two urns containing sticks of incense provide evidence of the veneration of the site, which the Berita Minggu article says attracts visitors of all races. Umi does confirm this, telling us that there are indeed visitors who come from as far as Europe, who offer prayers at the site.

Yellow is seen along with the colour green.

Before we leave, we ask Umi about the significance of the green seen on some of the graves. Umi tells us that they are of descendants of “shaikhs” from Iraq, related to Muslim holyman Habib Noh (of Keramat Habib Noh). Whether it is completely true or not is hard to establish. She adds the grave of an infant seen under the tree in the middle of the compound, is that of a grandchild of Habib Noh. As we thank Umi for her information and turn to leave, Umi adds that the tree is a holy one which should never be cut down.

URA’s Draft Master Plan 2013 shows the Keramat Bukit Kasita area as a reserve site.

Whether or not the tree will ever be cut down, would depend very on whether the site and the wealth of history that comes with it is discarded in the same way much of what made us who we as Singaporeans are has been sacrificed for the glitter of the soulless world we have come to embrace. What is known today, based on the latest (2013) draft of the URA Master Plan, is that the site is a reserved site for which there are no immediate plans. In that there is hope that what may be a link we have to a world we might otherwise have lost touch with, may somehow survive.

See also:

A Straits Times Article published on 6 Dec 2013:

HDB estate with grave links to the past. Muslim burial site in Bukit Purmei holds historical, spiritual significance.