There is little doubt that Singapore’s port has been a key driver of its success. The roots of the port as we know of it today were really laid by commercial dock companies established in the mid-1800s, chief amongst which were the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company and the Patent Slip and Dock Company (later the New Harbour Dock Company). Their possession of wharfage originally put up to support repair and resupply activities in the decade that preceded the opening of the Suez Canal, placed Singapore in an excellent position to meet the growth in shipping that followed and the advances in ship technology that had already been taking place.

Through consolidation, a duopoly was formed between the two dock companies before collaboration, first through a somewhat monopolistic joint-purse arrangement and eventually, through a merger saw to the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company emerging as a single big player in the provision of port and ship repair services in the final years of the nineteenth century. A direct result of this was the Straits Settlements government expropriation of the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company and the formation of Tanjong Pagar Dock Board . As a state-controlled body run with the interests of Singapore in mind, the board which morphed into the Singapore Harbour Board (SHB) and from 1964, the Port of Singapore Authority (PSA), was able to develop the port in a structured manner that was necessary to meet the challenges that were to follow.

Today, all that seems left to tell the story of the port’s origins are a handful of historical assets and former graving docks that now enhance residential developments around Keppel Bay as water features. Among the artefacts are those that came into the possession of Mapletree during the corporatisation of PSA. These include a steam crane that can now be found outside the revamped and somewhat unfriendly former St James’ Power Station, now the Singapore headquarters of Dyson. What could be thought of as another piece in the jigsaw would the former residence of the Chairman of SHB. This sits somewhat forlornly in isolation, in a quiet corner on the southern slope of Mount Faber. What I find especially interesting about the mansion is that it stands to recall the original players in the port’s operations having been completed just as the ball on the eventual formation of the Tanjong Pagar Dock Board was set in motion and is thus a marker of a significant point in the port’s history.

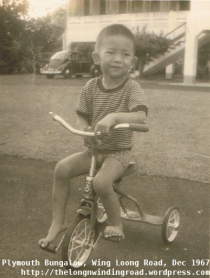

The house in question, lies close to the reservoir that was (allegedly) rediscovered in 2014, at 11 Keppel Hill. Completed in the final years of the 1800s and on land that was owned by the New Harbour Dock Company, it would have been erected to house the company’s most senior manager, being the largest of a cluster of new residences designed by Lermit and Westerhout that company had been in the process of erecting around and after 1897. While I have not come across plans for the house at 11 Keppel Hill, there seems to be several similarities in the plans developed by the architects for the other bungalows. This includes a central air and light well (if I can call it that) that is topped by a jack roof. A mention of what appears to be the house in question can also be found in a 1899 newspaper article. That describes a climb made by a party from the dock company from a reservoir it was constructing on the slopes of Mount Faber to the site of its “new house”. A description of its location of the house was also provided, with the house being “overlooked by the Mount Faber flagstaff”, and that it commanded a “splendid view of New Harbour and its surroundings.” The house, is the only one of the cluster of residences, one of which was Keppel Bungalow, that has been left standing.

With the amalgamation of the two dock companies, the house was named “Keppel House” and housed the Tanjong Pagar Dock Company’s Resident Civil Engineer, a position that was created in 1901 with the extensive construction works that the company had embarked on in mind. The first to hold the position was a Mr J Llewelyn Holmes, who left the position in June 1903. Holmes’ replacement, Mr Alan Railton, was known to have taken up residence at Keppel House.

Having been left vacant following the expropriation, Keppel House was then put up for rent before becoming the official residence of the Chairman of the SHB some time around 1918. It was then already occupied by Mr Stanley Arthur Lane. Lane’s move into the house occured sometime around 1916. A civil engineer, once of Sir John Jackson and Company, Lane came to Singapore late in 1907 to take up the role of Assistant Manager with the Tanjong Pagar Dock Board. Often acting as the Chairman of the Singapore Harbour Board in the absence of his predecessor John Rumney Nicholson, Lane’s appointment as Chairman came in 1918.

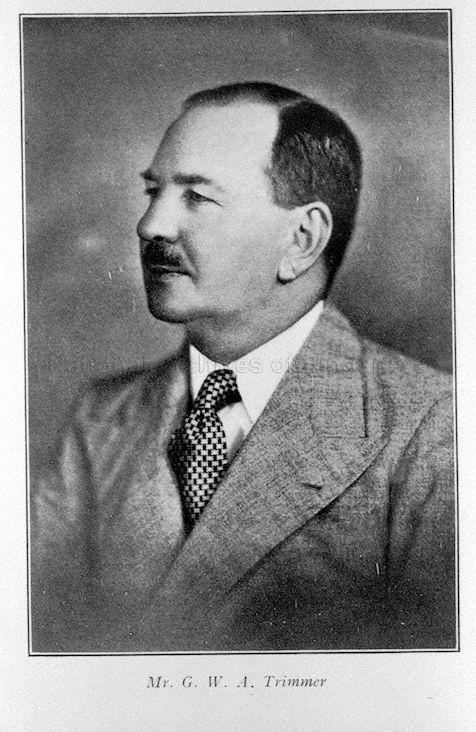

Keppel House most eventful years would come with the appointment of Mr George Trimmer — Sir George Trimmer from 1937, as Chairman upon Lane’s retirement in 1923. Trimmer retired in 1938, having overseen a massive port expansion programme that added almost a kilometre of new wharfage to accommodate large ocean-going vessels and added a number of new transit godowns. Trimmer was known to be an excellent host. It was also during Trimmer’s tenure at Keppel House that the nearby reservoir doubled up as a private swimming pool for the house’s residents and its guests.

An especially interesting event that took place during Trimmer’s stay in Keppel House was the successful transmission of both live and recorded music from it to a shortwave transmitter several miles away and then over the air. The experiment was conducted by an amateur radio broadcaster, who was also an employee of SHB, Robert Earle. Earle ran a radio station, V1SAB, with his wife for several years in the 1930s, broadcasting late in the evening twice a week.

Trimmer’s successor was Mr H K Rodgers, whose confirmation as Chairman and General Manager of the SHB was confirmed in August 1939 just as the dark clouds of war gathered over Europe. Rodgers would soon find himself caught up in the SHB’s own preparations for war. Keppel House would itself become a venue for events connect with the war in Europe and later, with the war’s arrival to Singapore’s shores. The performance of Dutch choir at a 1941 Christmas party thrown by Rodgers, saw guests, which reported numbered a hundred, join in the singing of Silent Night, Holy Night and Noel. Rodgers, would soon find himself organising an evacuation of SHB’s European staff, many of whom left Singapore on board the Bagan — a Penang ferry — on 11 February 1942 with Singapore’s fall seemingly imminent. Rodgers, who saw to the organisation of the evacuation from his residence, would himself leave Singapore early on 14 February 1942 — a day before Singapore’s inglorious fall — on the Tenggaroh, a launch that belonged to the Sultan of Johor. Rodgers eventually found his way to Australia, having made his way to Sumatra on the Tenggaroh. He returned to Singapore in 1946 to take up the role of the Managing Director of United Engineers Limited, a firm which operated a shipyard at Tanjong Rhu.

The Japanese Occupation, saw the operation of SHB’s repair facilities as the Syonan Shipyard by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) with staff from MHI’s Kobe yard. The first batch of MHI employees arrived in Singapore in March 1942 and immediately set about the task of restoring the damaged facilities. The working conditions at the yard took their toll on the MHI staff. At the end of 1944, some 15% of MHI employees sent to Singapore had either perished or return home due to illness. Among those who died was an engineer whose tomb can be found near Keppel House. It is quite probably that the engineer, as well as other members of MHI’s Syonan Shipyard’s senior staff, were in residence at Keppel House during this time.

After the war, the house reverted to being a residence for the SHB Chairman with Mr H B Basten being its first post-occupation resident. The arrangement would end in 1964 with the formation of PSA. The house found several uses over the years, becoming the PSA Central Training School in the 1970s, following which it was leased out as offices. Its tenants included a management consulting firm and an architectural firm who maintained flats on the upper floor for its staff. The house, which is currently vacant, was part of a group of houses on the southern ridges that were given conservation status in 2005.

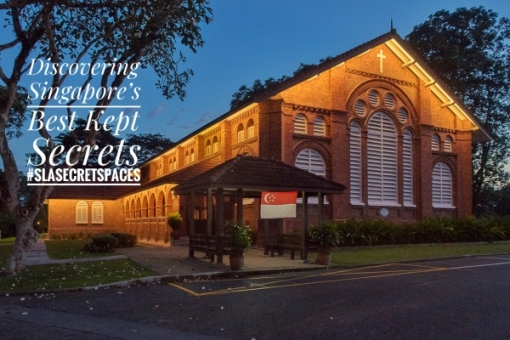

This visit to Keppel House was carried out with the kind permission of the Singapore Land Authority.

Inside and around the house :