Singapore had a brief love affair with the Concorde. Arguably the only supersonic passenger aircraft to be successfully deployed, a London to Singapore was operated by its National airline, Singapore Airlines, in partnership with British Airways for a few years at the end of the 1970s. The aircraft’s first flight over Singapore however, goes back to 1972, a year that was especially memorable for several events. I came across a wonderful photograph of that first flight some years back, one that in freezing the Concorde over a Singapore that in 1972 was at the cusp of its own reach for the skies, captured the lofty aspirations of the aircraft’s developers and of the city seen below it

The photo of Concorde 002 over the old city centre of Singapore during its month-long demonstration tour of the Far East in June 1972 (online at http://www.concordesst.com/).

1972 was the year I was in Primary 2. I was seven, going on eight, ten months older than the newly independent Singapore, and at an age when any machine that sped were about the coolest things on earth. I was also finding out that going to school in the afternoon was quite a chore. Unlike the morning session I was in the previous year, there was little time for distractions and TV. School days were just about tolerable only because of the football time it could provide before classes started each day and unlike the previous school year, great excitement seemed to come only away from school, and the highlight of the year would be one that I would have to skip, “ponteng” in the language used among my classmates, school for.

Football was very much part of the culture at St. Michael’s School, the primary school I attended.

The buzz the Concorde created, even before it came to Singapore in June of the year, left a deep impression with the boys I kept company with and the paper planes we made featured folded-down noses that resembling the Concorde’s droop nose – even if it made they seemed less able to fly. I was fortunate to also see the real McCoy making a descent at Paya Lebar Airport, one that was much more graceful than any of the imitations I made. I have to thank an uncle who was keen enough to brave the crowds that had gathered at the airport’s waving gallery for that opportunity. The event was a significant one and took place in a year that was especially significant for civil aviation in Singapore with the split of Malaysia-Singapore Airlines or MSA, jointly operated by the two countries taking place in the background. The split would see the formation of Mercury Singapore Airlines on 24 January to fly Singapore’s flag. The intention had been to ride on the established MSA name, which was not too well received on the Malaysian side, prompting the renaming of the new MSA to Singapore Airlines (SIA) on 30 June 1972, a point from which the airline has never looked back.

What might have been.

The building that housed MSA and later SIA is prominent in the 1972 photograph, the MSA Building. Completed in 1968, the rather iconic MSA and later SIA Building was one built at the dawn of the city’s age of the skyscraper. The building was a pioneer in many other ways and an early adopter of the pre-fab construction technique. A second building in the photograph that also contributed to frenzy was the third Ocean Building, then under construction. The Ocean was to be the home of another company that was very much a part of Singapore’s civil aviation journey: the Straits Steamship Company. It was during the time of the already demolished Ocean Building that preceded the third that the company set up Malayan Airways in 1937. The airlines, which would only take off in 1947, became Malaysian Airways in 1963, and then MSA in 1965. The company, a household name in shipping, is now longer connected with sea or air transport in its current incarnation as Keppel Land. Other buildings marking the dawn of the new age seen in the photograph include the uncompleted Robina House and Shing Kwang House, and also a DBS Building in the early stages of erection.

The fast growing city, seen at ground level in 1972 (Jean-Claude Latombe, online at http://ai.stanford.edu/~latombe/)

The completed third Ocean Building (left), seen in July 1974 (photo courtesy of Peter Chan).

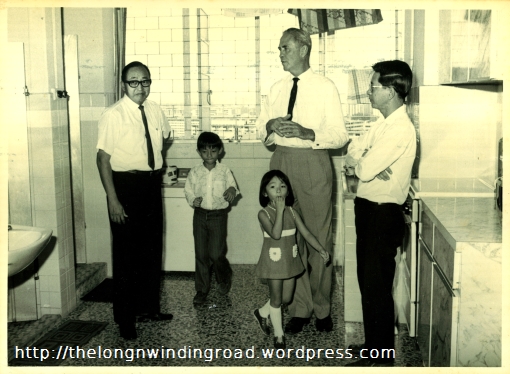

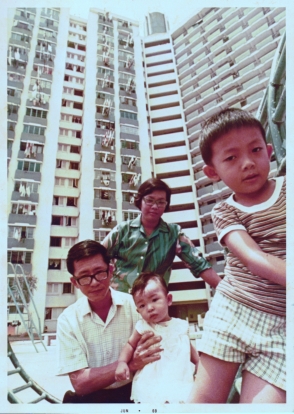

It was several months prior to the the Concorde’s flight and just four weeks into school, that I would find myself skipping classes for what was to be the highlight of the year and of my childhood: the visit of the Queen, Elizabeth II of England, Price Phillip, and Princess Anne, to the 3-room Toa Payoh flat I had called home. As its was in the case of several other visiting dignitaries, Her Majesty’s programme included a visit to the rooftop viewing gallery of the Housing and Development Board’s first purpose-built “VIP block”. The gallery was where a view of the incredible success Singapore had in housing the masses could be taken in and a visit to a flat often completed such a visit and living in one strategically placed on the top floor of the VIP block had its advantages. Besides the Royal family, who were also taken to a rental flat on the second floor of Block 54 just behind the VIP block, Singapore’s first Yang di-Pertuan Negara and last colonial Governor, Sir William Goode, also dropped by in 1972. The flat also saw the visits of two other dignitaries. One was John Gorton, Prime Minister of Australia in 1968 and the other, Singapore’s second president, Benjamin Henry Sheares, and Mrs Sheares in 1971.

The Queen, the Duke of Edinburgh and Princess Anne, in the kitchen of my flat on 18 February 1972.

The Queen at the Viewing Gallery on the roof of Block 53 Toa Payoh on 18 February 1972.

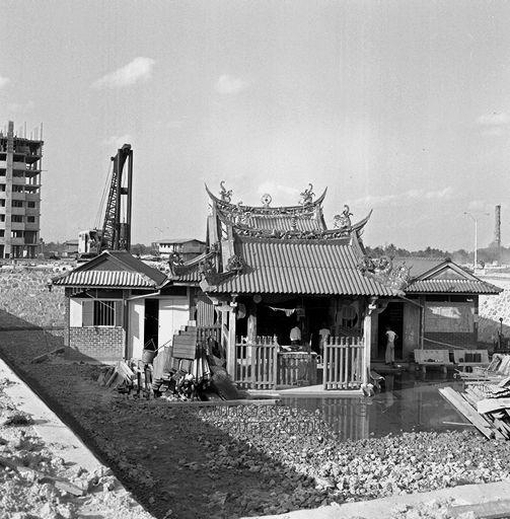

One thing being in the afternoon session developed was the taste I acquired for epok-epok, fried curry puffs that are usually potato filled. Sold by a man who came around on a bicycle at dismissal time, the pastries that he vended – out of a tin carried on the bicycle – were ones to die for. They were made especially tasty the vendor’s special chilli-sauce “injected” in with a spout tipped bottle and well worth going hungry at recess time, to have the 10 cents the purchase required, for. Being in the afternoon session, also meant that the rides home from school on the minibus SCB 388, were often in the heavy traffic. The slow crawl, often accompanied by the deep vocals of Elvis Presley playing in the bus’ cartridge player, permitted an observation of the progress that was being made in building Toa Payoh up. Much was going on in 1972 with the SEAP games Singapore was to host in 1973 just around the corner. Toa Payoh’s town centre, also the games village, was fast taking shape.

A view over Toa Payoh around 1972.

Toa Payoh’s evolving landscape stood in stark contrast to its surroundings. To its south, across the Whampoa River, was Balestier – where suburbia might have ended before Toa Pyaoh’s rise. That still held its mix of old villas, shophouses, and a sprinkling of religious sites. The view north on the other hand was one of the grave scattered landscape of Peck San Teng, today’s Bishan, as would possibly have been the view west, if not for the green wall of sparsely developed elevations. On one of the hills, stood Toa Payoh Hospital, in surroundings quite conducive to rest and recovery. Potong Pasir to Toa Payoh’s east had still a feel of the country. Spread across what were the low lying plains that straddled one of Singapore’s main drainage channels, the Kallang River, the area was notorious for the huge floods that heavy rains would bring. When the area wasn’t submerged, it was one of green vegetable plots and the zinc topped structures of dwellings and livestock pens.

The grave dominated landscape north of Toa Payoh – with a view towards Toa Payoh (SPH photo, online at http://news.asiaone.com/).

Potong Pasir (and Braddell Road) during the big flood of 1978 (PUB photo).

Another main drainage channel, the Singapore River, was a point of focus for the tourism drive of 1972, during which two white statues came up. Representations perhaps of the past and the future, the first to come up was of a figure from its colonial past. The statue of Raffles, placed at a site near Empress Place at which Singapore’s founder was thought to have first came ashore, was unveiled in February. The second, was the rather peculiar looking Merlion and a symbol perhaps of new Singapore’s confused identity. This was unveiled at the river’s mouth in September. A strangest of would be National symbols and with little connection to Singapore except for its head of a lion, the animal Singapore or Singapura was named after, the creature was made up in a 1964 tourism board initiated effort. Despite its more recent origins, the statue has come to be one that tourists and locals alike celebrate and that perhaps has set the tone for how Singapore as a destination is being sold.

The Merlion at its original position at the mouth of the Singapore River (seen here in 1976).

The Merlion at its position today, staring at the icons of the new Singapore.

1972 was a year that has also to be remembered for the wrong reasons. Externally, events such as the tragic massacre of Israeli Olympians in Munich, brought much shock and horror as did the happenings closer to home in Indochina. There were also reasons for fear and caution in Singapore. Water, or the shortage of it was very much at the top of the concerns here with the extended dry spell having continued from the previous year. There were also many reasons to fear for one’s safety with the frequent reports of murders, kidnappings and shootouts, beginning with the shooting to death of an armed robber, Yeo Cheng Khoon, just a week into the year.

The darkest of the year’s headlines would however be of a tragedy that seemed unimaginable – especially coming just as the season of hope and joy was to descend. On 21 November, a huge fire swept through Robinson’s Department Store at Raffles Place in which nine lives were lost. The devastating fire also deprived the famous store of its landmark Raffles Place home and prompted its move to Orchard Road. This perhaps also spelled the beginning of the end for Singapore’s most famous square. In a matter of one and a half decades, the charm and elegance that had long marked it, would completely be lost.

Robinson’s at Raffles Place, 1966.

The burnt shell of Robinson’s (SPH photo online at http://www.tnp.sg/)

Another tragic incident was the 17 September shooting of the 22-year-old Miss Chan Chee Chan at Queensway. While the shooting took place around midday, it was only late in the day that medical staff attending to Miss Chan realised that she had been shot. A .22 calibre rifle bullet, lodged in her heart, was only discovered after an x-ray and by that time it was too late to save her.

Just as the year had started, shootouts would be bring 1972 to a close in which four of Singapore’s most wanted men were killed. At the top of the list was Lim Ban Lim. Armed and dangerous and wanted in connection with the killing of a policeman, a series of armed robberies on both sides of the Causeway, Lim was ambushed by the police at Margaret Drive on 24 November and shot dead. Over a nine-year period, Lim and his accomplices got away with a total of S$2.5 million. An accomplice, Chua Ah Kau escaped the ambush. He would however take his own life following a shootout just three weeks later on 17 December. Having taken two police bullets in the confrontation near the National Theatre, Chua turned the gun on himself.

The case that had Singapore on tenterhooks due to the one and a half month trail of violence and terror left by the pair of gunmen involved, would play itself out just the evening before the gunfight involving Chua. It was one that I remember quite well from the manner in which the episode was brought to a close in the dark and seemingly sinister grounds of the old Aljunied al-Islamiah cemetery at Jalan Kubor. The trigger-happy pair, Abdul Wahab Hassan and his brother Mustapha, crime spree included gun running, armed robbery, gunfights with the police, hostage taking and daring escapes from custody (Abdul Wahab’s from Changi Prison and Mustapha’s from Outram Hospital). Cornered at the cemetery on 16 December and with the police closing in, Abdul Wahab shot and killed his already injured brother and then turned the gun on himself.

The Aljunied Al-Islamiah Cemetery off Jalan Kubor and Victoria Street, where two gunmen met their deaths in 1972.

Besides the deaths of the four, quite a few more armed and dangerous men were also shot and injured as a result of confrontations with the police. A 23 December 1972 report in the New Nation put the apparent rise in shootouts to the training the police had received to “shoot from the hip, FBI style”. The spate of crimes involving the use of firearms would prompt the enactment of the Arms Offences Act in 1973, which stipulates a mandatory death penalty for crimes that see the use of or the attempt to use a firearm to cause injury.

The tough measures may possibly have had their impact. The use firearms in crimes is now much less common. This has also brought about an increased the sense of safety in Singapore, as compared to 1972. Many who grew up in that age will remember being warned repeatedly of the dangers on the streets, particularly of being kidnapped. The same warnings are of course just as relevant today, but the threat was one that could be felt. Many stories of children disappearing off the streets were in circulation and that heightened the sense of fear. While many could be put down to rumour, there was at least one case of a child being abducted from a fairground, that I knew to be true. There were also many reports of actual kidnappings in the news, including one very high profile case in 1972 that saw the abduction of a wealthy Indonesian businessman. The businessman was released only after a ransom was paid.

Singapore in 1972:

- Singapore (1972) by Jean-Claude Latombe

- Singapore 1972 – an album on Flickr by Polyrus

- Singapore 1957 on – an album on Flickr by Gary Denvers

- The 1972 General Elections

- The Queen visiting Singapore in 1972 (AP News Footage showing the Queen’s arrival at Block 53, Toa Payoh)

- The Queen visiting Singapore in 1972 (AP News Footage showing the Queen at the viewing gallery of Block 53, Toa Payoh)

- The Queen visiting Singapore in 1972 (Local News Footage showing the Queen’s arrival at the flat I lived in)

+TPY_S4_SitePlan_10May2013.jpg)