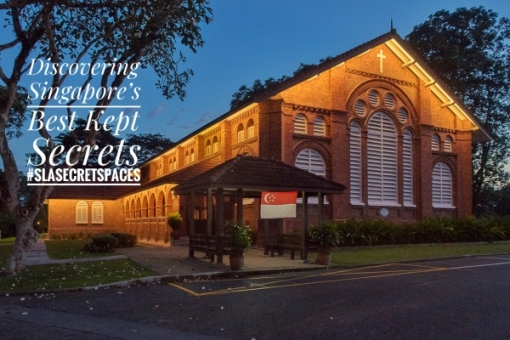

One of Singapore’s urban spaces in which there is always much to discover is what we have come to know as Chinatown. It may seem that Chinatown today, cleansed of the people and business that made it what it was, is without a soul. It does indeed seem in many parts like a neighbourhood that has been conserved and revived more to draw the tourist dollar than to preserve the memories it holds, but it is in some of the quieter streets of the area designated as a Chinese settlement by Raffles not long after modern Singapore’s founding, that we do find many traces, some still very much alive, of a world that for most part has ceased to exist.

Part of the Thian Hock Keng Temple on Telok Ayer Street – one of the traces left behind by a long forgotten time.

One especially quiet area, seemingly in an area cut off from the busier streets of the neighbourhood, is where there is a wealth of these reminders. It was on a street in the area, now caught between the past and the present, Telok Ayer Street, where in fact the first chapters in the story of Singapore from the perspective of our forefathers did in fact begin in the early days that followed the arrival of the British. The street’s name, Telok Ayer, suggests proximity to the sea – “telok” being Malay for “bay” and “ayer” the word for “water”, although a field of glass and steel and beyond that, the makings of a future city, puts some distance between it and the waters of the Straits of Singapore. Given that, it may surprise some that the land on which the street was built was one where waves of Telok Ayer Bay might have washed up to – and it was where many who made the long and perilous journey in search of fortune in the early days of Singapore, would have first set foot on the island.

Non-organic business now occupy many of the conserved shophouses in the area today.

Telok Ayer Street today would in all likelihood, look little like the street the early immigrants made landfall on. But despite the many changes that have come about including the land reclamation exercise that took place from 1879 to 1887 during which its lost its shoreline and more recent urban redevelopment and conservation efforts during which its residents and organic businesses were moved out, it still very much alive with many reminders left by our early founders and very much a living monument to their memory, one which perhaps can serve in place of that intended monument to our early founders that was never built.

The Jackson Plan of 1822 shows the location of Telok Ayer Street relative to the shoreline.

A diorama of Telok Ayer Street in the early days of modern Singapore showing where the shoreline was. The low building across from the Chinese Opera stage is the Fuk Tak Chi Temple built by Hakka immigrants and used by both Hakkas and Cantonese. It is now the Fuk Tak Chi Museum.

The most significant reminder that we find on the street would be the Taoist Temple the name in Chinese of which translates into of Heavenly Bliss (Thian Hock Keng, 天福宫, in the Hokkien or Fujian dialect). The temple is probably the most popularly visited religious site for tourists coming to Singapore and is a joy to behold. Dedicated to the protector of sailors and fishermen, the Taoist Goddess of the Sea, MaZu (妈祖), the temple’s origins can be traced to the earliest days of modern Singapore. It was built on the site of a joss house put up around 1820/21 by early Hokkien immigrants close to the first landing points to allow thanks to be offered to the goddess for protection provided over the long sea voyage.

The side of the main hall of the temple. The temple is a fine example of Minan arhcitecture, characterised by its curved “swallow-tail” roof ridge.

The temple we see today, even with alterations made during a 1906 renovation in which western style floor and wall tiling was added), must be counted as one of the best examples of Southern Chinese Minan temple architecture (found on many Hokkien built temples such as the Hong San See) in Singapore. Distinctive features of Minan temple architecture are the curved “swallow tail” roof ridge and the intricate timber post and beam structure. Completed in 1842, the main altar (of which photographs of are not permitted) has two statues of Ma Zu. One – the darker and smaller of the two, which dates to building’s construction, is said to have been blackened by burning incense offered at the altar over the many years of the temple’s existence.

Lanterns for the Chinese New Year at the Thian Hock Keng.

The temple is also home to several other deities and provides the visitor with a good appreciation of the folk religious practices the Hokkien (and other southern Chinese) immigrants brought in with them. One of the deities, is the popularly worshiped Bodhisattva of Thousand Hands and Thousand Eyes�, more commonly referred to as the Goddess of Mercy, Kuan Yin. The altar dedicated to her is found behind the main altar, housed in a beautiful part of the temple complex. Other deities include Kai Zhang Seng Wang (The Sacred Governor Kai Zhang), Cheng Huang Ye (City God) flanked by the Da Er Ye Bo (The Two Great Generals, 大二爷伯), or, Qi Ye Ba Ye, 七爷八爷 (which translates to Seventh and Eight Lords). More on the deities can be found at the temple’s website.

The altar dedicated to Kuan Yin in the Thian Hock Keng.

Another view of the altar dedicated to Kuan Yin.

The altar where Cheng Huang Ye (City God) is, flanked by the two Great Generals.

A close-up of Qi Ye.

The temple’s construction which started in 1839 could not have been done without the generous donations made by the members of the early Hokkien Chinese community. Chief among the donors was Tan Tock Seng, a well known philanthropist and an early immigrant from Malacca, best known perhaps for the paupers’ hospital he helped set up and which is now named after him. As was the case with many early temples, Thian Hock Keng served to also provide social support for the community. It initially housed the oldest Hokkien clan, the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan (Hokkien Clan Association), which has since moved across the street (it was apparently where a Chinese opera or wayang had been positioned in the early days of the temple). The Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan still runs the Thian Hock Keng.

Two types of Door Gods guard the entrance to the Thian Hock Keng.

Besides the commonly found ones, there the the more passive looking eunuch Door Gods more to welcome the good – commonly found in temples where the main deity is a goddess.

On the temple’s right (seen from the deity’s perspective), on what is considered part of the temple complex is the beautifully built Chong Hock Pavilion and Chung Wen (or Chong Boon) Pagoda. Access is via a normally closed separate entrance, the Chong Boon Gate, on Telok Ayer Street. The pagoda (and gate) was built in 1849 and housed what is said to be the earliest Chinese private school in Singapore, the Chong-Wen Ge (or the “Institute for the Veneration of Literature”). The Chong Hock Pavilion, built in 1913, housed the Chong Hock Girls’ School which was set up in 1915. The school in 1930 was moved partly across the street (where the Hokkien Association Building is today). It has since been renamed Chongfu school and is now located in Yishun.

The entrance to the Chong Hock Pavilion and the Chung Wen Pagoda, the Chong Boon Gate .

The Chong Hock Pavilion.

The temple complex, which was gazetted as a National Monument in 1973, went through a major restoration effort from 1998 to 2000, during which craftsmen from China were employed. Those efforts won it an Honourable Mention for the UNSECO Asia-Pacific Heritage Awards in 2001. An important discovery made during that restoration was a calligraphic scroll, with the imperial seal of Emperor Guang Xu of the Qing Dynasty. Placed in a previously unidentified scroll holder on a panel, which incidentally is a display copy of the scroll placed above the main altar, the scroll was presented to the temple by the Emperor in 1907.

The Chong Boon Gate and the Chung Wen Pagoda.

Besides the Thian Hock Keng, several other important religious or clan buildings established by the immigrants can also be found along the same street. One was a Hakka built temple, the Fuk Tak Chi temple, dedicated to the Earth God Da Bo Gong. Although the temple has since ceased to operate, its building can be still found and is part of the Far East Square complex and is a reconstruction built in the Hokkien style with a curved roof ridge. Its main hall and entrance is said to have been constructed in the style of a Chinese Magistrate’s Court as a symbol of power and authority.

The Fuk Tak Chi Museum.

The temple which dates back to 1824, served both the Hakka and Cantonese communities (which tells of the close relationship between the two communities in Singapore). Closed in 1994, it has since been restored and converted into a museum. A important artifact that is still housed in the building is a wooden screen found at its entrance. Just a few doors away from the Fuk Tak Chi, is another important link to the early Hakka immigrants, the Ying Fo Fui Kun. This is a Hakka clan association which was founded in 1822. “Ying Fo” translates into “mutual co-operation for peaceful co-existence” which provides a clue to why clan associations were established. The building which dates back to a reconstruction in 1843/44, underwent renovation in 1997 and was gazetted as a National Monument in 1998.

Inside the Fuk Tak Chi Museum.

The wooden screen at the entrance of the Fuk Tak Chi.

Odd as it may seem, being on the fringe of Chinatown, one finds on the very same street, two structures erected by Chulia Muslim immigrants who originated from the Coromandel Coast of India. The structures are of course not out-of-place – the Chulias, many of whom were merchants, very naturally found spaces to conduct their businesses amongst the Chinese traders along what was the seafront. The area would also have been close to the original area Raffles has set aside for the Chulia settlement just north of the Chinese settlement.

The Al-Abrar Mosque built by the Chulias.

One of these structures, the Al-Abrar Mosque which sometimes is referred to as Masjid Chulia or Chulia Mosque, is still in use (not to be confused with another Chulia Mosque Masjid Jamae in South Bridge Road). The mosque was first set up in 1827 by Tamil Muslim immigrants, and is also known in Tamil as the Kuchu Palli (kuchu means “hut”, palli means “mosque’). The current building was completed in 1855 and was gazetted as a National Monument in 1974.

The former Nagore Durgha Shrine.

The other structure built by the community, the former Nagore Durgha Shrine, is one that will certainly catch the eye. Sitting prominently at the corner of Telok Ayer and Boon Tat Streets, it had long been closed to the public. The former mashhad or memorial, has since May 2011 been reopened as the Nagore Dargah Heritage Centre. Built between 1827-1830, the Nagore Durgha was built as a memorial to a Sayyid Abdul Qadir Shahul Hamid, a holy man from Northern India based at Nagore in Tamil Nadu. The mashhad, originally known as Shahul Hamid Durgha, is rather distinctive from an architectural viewpoint. It features a mix of east and west – Palladian features on the lower part of the building, topped with an Islamic style upper part, and is thought to be an attempt to replicate the original Nagore Durgha shrine in Negapatnam (Nagapattinam) which is just south of Nagore. The heirtage centre is well worth a visit. Besides the insights it offers to the early days of the Indian Muslim community in Singapore, and their cultural and religious practices, there is also an opportunity to enjoy the beautiful column and arch lined interior that is illuminated by light streaming through its stained glass windows. The now beautifully restored Nagore Durgha has been a National Monument since 1974.

Inside the Nagore Durgha.

Walking around today, it would be easy to miss one of more recently gazetted monuments on the street, the last of the monuments I wish to mention. That, the former Keng Teck Whay, lies hidden behind hoardings, somewhere between the Nagore Durgha and the Thian Hock Keng. With a distinguishing three tiered pagoda which has octagonal plan upper floors on a square base, it would certainly be one to admire – if not for the much needed restoration work that is going on at the moment. Built to house the Keng Teck Whay, a self-help association set up by Hokkien-Peranakan merchants from Malacca in 1831, the buildings we see today came up between 1847 and 1875 and were constructed by traditional Chinese craftsmen in the Minan style. The building at the rear which is said to feature details borrowed from Teochew style architecture and was used as an ancestral hall. The Taoist Mission has since taken over the buildings which were in rather a dilapidated state. Repairs and restoration of the buildings are currently being done and the mission will run the complex as the Singapore Yu Huang Gong, 新加坡玉皇宫, or Temple of Heavenly Jade Emperor.

An aerial view of the former Keng Teck Whay (source: http://pictures.nl.sg). All rights reserved. Preservation of Monuments Board Singapore 2010).

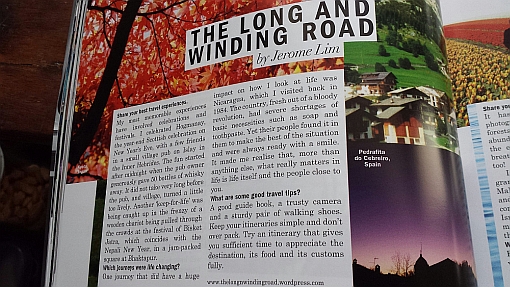

With the pace of change not just robbing us, residents of what has become an increasing congested island, of places and experiences that help us connect with a country we call home, but also replacing many familiar places with that brave new world we find hard to identify with, it is perhaps only in places such as this we can hold on to. While they perhaps do not hold the personal memories and experiences we may hold dear, they do hold the memory of who we are as a nation, of where we came from and how we got here, and most importantly, of what made Singapore, Singapore.