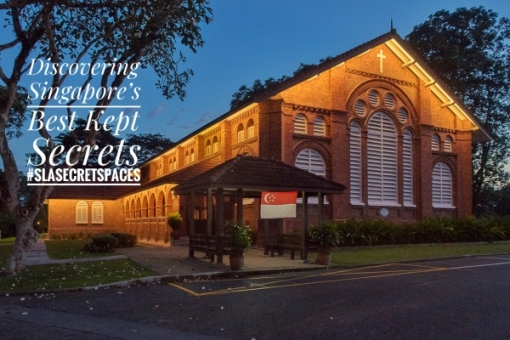

Two beautiful conservation houses, Atbara and Inverturret at No 5 and No 7 Gallop Road, grace the newly opened Singapore Botanic Gardens Gallop Extension. Both wonderfully repurposed, Atbara as the Forest Discovery Centre and Inverturret as the Botanical Art Gallery, they are among the oldest and finest surviving examples of residential properties that English architect Regent Alfred John (R A J) Bidwell designed in Singapore.

Bidwell, who had an eventful but short two-year stint in the Selangor Public Works Department (PWD) as Chief Draughtsman and assistant to Government Architect A C Norman, came across to Singapore in 1895 to join pre-eminent architectural firm Swan and Maclaren. In a matter of four years, he became a partner in the firm; an arrangement that lasted until 1907. Bidwell would continue his association with the firm as an employee until 1912. His 17 years with Swan and Maclaren, was one marked by the string of notable contributions that he made to Singapore’s built landscape. His architectural works include many of Singapore’s landmarks of the early 20th century, which include the Goodwood Park Hotel — built as a clubhouse for the Teutonia Club; Victoria Theatre and Victoria Memorial Hall (the theatre component of the pair was a modification of a previously built Town Hall that also gave it an appearance similar to the 1905 erected Victoria Memorial Hall; and Stamford House — built as Whiteaway and Laidlaw Building in 1905. Also notable among his contributions were several buildings that have since been demolished, one of which was the old Telephone exchange on Hill Street that was designed in the Indo-Saracenic style.

The Indo-Saracenic style was something that Bidwell would have been extremely familiar with, having been heavily involved in the design of the Government Offices in Kuala Lumpur or KL, now the Sultan Abu Samad Building. Hints of the style are also found in one of the first design efforts in Singapore, which is seen in the unique set of piers on which Atbara is supported. The bungalow, along with several others that Bidwell had designed, is thought to have influenced the designs of numerous government, municipal and company residences, the bulk of which were constructed from the 1910s to the 1930s. Many of these are still around and are often erroneously referred to as “black and white houses”, a term that is more descriptive of their appearance — many are painted white with black trimmings — rather than a description of a their style or of a particular architectural style (see also: The Eastern Extension Telegraph Company’s Estate on Mount Faber).

Atbara has in fact earned the distinction of being Singapore oldest “black and white house” even if it does display a variety of architectural influences; influences that are also seen in many of the designs of the various residences. Built in 1898, apparently for lawyer John Burkinshaw, Atbara’s piers, timber floorboards and verandahs are among the features or adaptations applied to the residences of the early 20th century, all of which were intended to provide their occupants with a maximum of comfort in the unbearable heat and humidity of the tropics. Many of these adaptations were ones borrowed from the bungalows of the Indian sub-continent, from plantation style houses, and also the Malay houses found in the region. There was extensive use of pitched-roofs, a feature seen in the then popular Arts and Crafts style that the English architects of the era would have been familiar with. These roofs lent themselves to drainage and the promotion of ventilation through convection when combined with generous openings. Tropical interpretations of the Arts and Crafts style were in fact widely applied to several residences built during the era.

Atbara, which early “to-let” advertisements had as having seven rooms, five bathrooms, with a large compound and with extensive views, came into the possession of Charles MacArthur, Chairman of the Straits Trading Company, in 1903. MacArthur added the neighbouring Inverturret soon after in 1906. Also designed by Bidwell, Inverturret rests on a concrete base and is of a distinctively different style — even if verandahs, ample openings and the pitched roof found in Atbara are in evidence.

The two properties were eventually acquired by the Straits Trading Company in 1923, who held it until 1990, after which both were acquired by the State. The houses had several prominent tenants during this period. Just before the Second World War, Inverturret briefly served the official residence of the Air Officer Commanding (AOC), Royal Air Force Far East, from 1937 to 1939. During these two years, Inverturret saw two AOCs in residence, Air-Vice Marshal Arthur Tedder and Air-Vice Marshal John Babington. Their stay in Inverturret was in anticipation of a much grander residence — the third of a trio that was to have been built to house each of the senior commanders of the three military arms. Two, Flagstaff House (now Command House) to house the General Officer Commanding, Malaya and Navy House (now old Admiralty House) for the Rear Admiral Malaya, were known to have been built.

From 1939 to 1999, both Atbara and Inverturret were leased to the French Foreign Office by the Straits Trading Company up to 1990 and following their acquisition in 1990, by the State up to 1999. Except for the period of the Japanese Occupation (it is known that Inverturret was used as a residence for the Bank of Taiwan’s Manager during the Occupation) and shortly thereafter, Atbara served as the French Consular Office and later the French Embassy, and Inverturret as the French Consul-General’s / French Ambassador’s residence. It was during this period that those like me, who are of an age when travel to France required a visa, may remember visiting Atbara. The process of obtaining a visa involved submitting an application with your passport in the morning, and returning in the afternoon to pick the passport and visa up, a process that was not too dissimilar to obtaining an exit permit at the nearby CMPB!

Atbara

Inverturret

R A J Bidwell and Kuala Lumpur’s Sultan Abu Samad Building

Built as Government Offices for the Selangor Government from 1894 to 1897, the Sultan Abu Samad building – a landmark in Kuala Lumpur was described as the “most impressive building in the Federated Malay States”. Although the architectural work for it has been widely attributed to A C Norman, the Selangor Public Works Department’s Government Architect, it is widely accepted that it was R A J Bidwell who developed the finer architectural details of its eye-catching Indo-Saracenic lines. Bidwell, who was assistant to Norman from 1893 to 1895, developed the plans with input from C E Spooner – the State Engineer, who directed that initial plans for the building be redone in what he termed as the “Mohammedan style”.

Bidwell’s disaffection with his position and salary, saw to him resigning from the Selangor PWD — as is reflected in his correspondence relating to his resignation. The Selangor PWD’s loss would turn into Singapore’s gain, with Bidwell moving to Singapore in 1895 to join Swan and Maclaren .