It is wonderful that technology allows the wealth of photographs that exist of a Singapore we no longer see to be shared. Those especially taken by those whose stay in Singapore was temporary, offer perspectives of places as they were that the local might have thought little of capturing. One of my favourite sets of photographs are those of a David Ayres. Shared through a Flickr album Oldies SE Asia containing some 250 photographs, they take us back to Mr. Ayres’ days in the Royal Navy and include many scenes of places of the Singapore of my childhood that I would not otherwise have been able to ever see again.

A part of Singapore we can never go back to. The view is of the waterfront and the Inner Roads from a vantage point just across the mouth of the Stamford Canal from Esplanade or Queen Elizabeth Walk. Land reclamation has since taken this view away, replacing it with a view that will include One Raffles Link and Esplanade Theatres by the Bay (David Ayres on Flickr).

Mr. Ayres interactions in Singapore came from his two stints at HMS Terror (now Sembawang Camp) in the Naval Base. The first in 1963/64, just about the time I was born, and again in 1966/67. Now 71, he finally managed a trip that he said he he just had to make having not been back to Singapore since he last saw it almost 50 years ago at the end of his second stint in 1967.

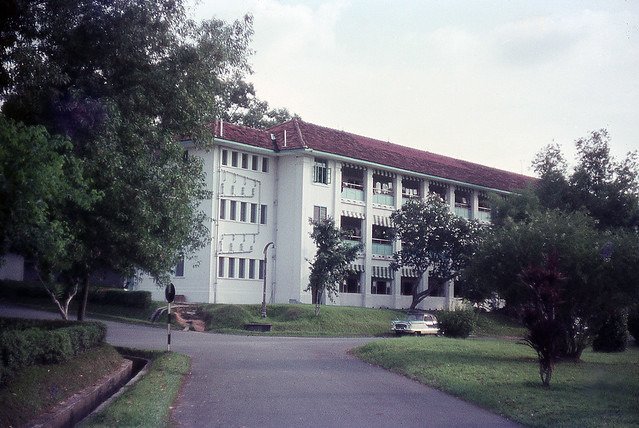

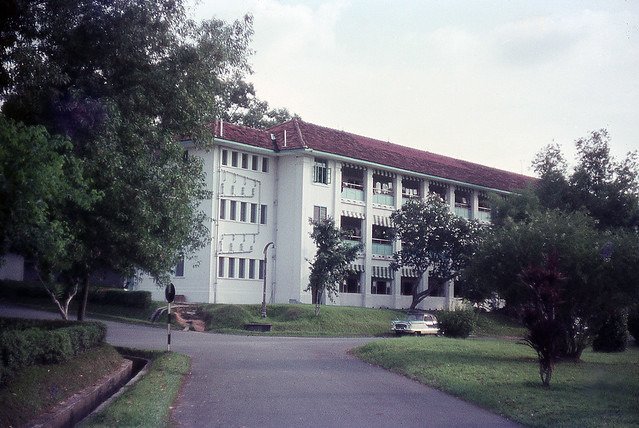

A HMS Terror (now Sembawang Camp) barrack block, one that is familiar to me as it was the same block I was accommodated during my reservist in-camp training stints in the 1990s (David Ayres on Flickr).

I managed to say a quick hello to Mr. Ayres during his short visit, managing a short chat with him at a coffee shop in what had once been Sembawang Village, an area that is quite well represented in Mr. Ayres’ set of photographs. Once a busy area of watering holes, shops and makeshift eating stalls located just across one of the main entrances to the huge Naval Base – an entrance used especially by personnel headed to HMS Terror, all that it has since been reduced to is the row of two-storey shophouses in which the coffee shop was at.

David Ayres (R), with his mate Phil and Nora, the founder of Old Sembawang Naval Base Facebook group, in the shadow of the Nelson Bar of today.

The Nelson Bar as seen in 1967 (David Ayres on Flickr).

It was interesting to learn that there was much Mr. Ayres could still recognise from his walk earlier in the day around the former Naval Base, a walk he did with his mate Phil with the help of Nora of the Old Sembawang Naval Base Facebook group. It is perhaps fortunate for Mr. Ayres that Sembawang, a part of Singapore he would have been most familiar with, is one of few places left in Singapore in which much of its past is still to be found in the present.

The Red House, as the Fleet Sailing Centre was referred to because of its red roof (David Ayres on Flickr).

The Red House today as seen from SAF Yacht Club. It’s red roof tiles have since been replaced by green ones and the sea pavilion is now in a rather dilapidated state.

A good part of the base housing still remains intact, as do the former dockyard and stores basin, both of which still operating under another guise. Part of HMS Terror is also still around, a part that is visible over its perimeter fence. There also is the former “Aggie Westons” on the hill across from the dockyard gates. This saw use as the Fernleaf Centre in the days when the NZ Force SEA had troops based in Sembawang and is now in use by HomeTeam NS as a recreation centre. A sea pavilion, which served as the Fleet Sailing Centre in the days of the Naval Base, is also still visible from the SAF Yacht Club. Referred to as the “Red House” for its red roof tiles, the pavilion has since been turned green and as observed by Mr. Ayres, now looks rather dilapidated.

‘Aggie Westons’ in David’s time in Sembawang, it became Fernleaf Centre during the days of the New Zealand Force SEA and is today used by HomeTeam NS as a recreation centre. David made a stop here during his recent visit to Sembawang (David Ayres on Flickr).

As we pored over some photographs Mr. Ayres had printed over glasses of lime juice, he also made mention that the row of shophouses we were at had not been around during his first stint at HMS Terror. One of the area’s last additions, it had been put up before Mr. Ayres came back for his second tour. It is in the row that several bars including the Nelson Bar were housed and was a popular drinking spot for servicemen up to the days when the New Zealand forces had a presence in the area. It is also worth mentioning that the cluster of stalls found in the area, popular as stopover for personnel looking for a quick bite, was where the improvised hawker dish we know as Roti John is said to have originated from.

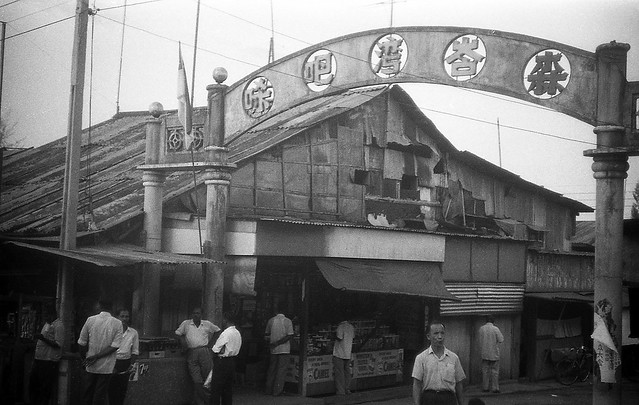

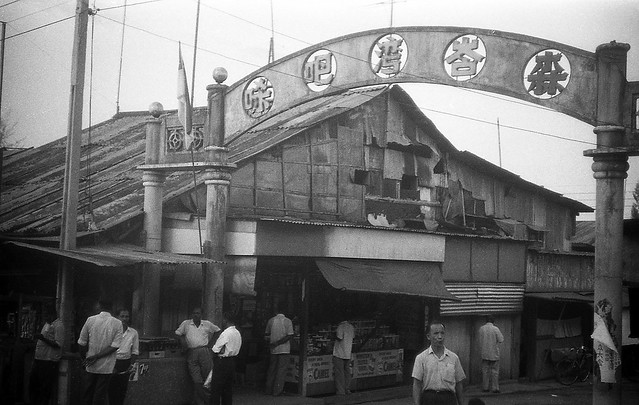

The cluster of food stalls at Sembawang Village, where Roti John was said to have been invented (David Ayres on Flickr).

Besides those in and around the Naval Base, Mr. Ayres captures include many other places that featured in my younger days; places in and around the city centre, then referred to as Singapore, as well as a few far flung places such as Changi. There are also scenes found in the set taken in peninsula Malaysia that are familiar to me from the drives my father was fond of making north of the Causeway. The photographs of the city centre have proved to be particularly fascinating to younger Singaporeans. One taken of Raffles Place in its landscape car-park rooftop garden days in the direction of Battery Road, made its rounds in 2012, going viral in Singapore. One impression of the modern city that had replaced the one in his photographs that Mr. Ayres and his friend Phil had, was of seeing very few elderly people in it; this perhaps is a manifestation of the disconnect with the brave new world that the city centre has become many in the older generation feel.

Mr. Ayres’ capture of Raffles Place in 1966 made its rounds around the internet in 2012 (David Ayres on Flickr).

Mr Ayres’ photographs have a quality that goes beyond simple snapshots. Well composed and often offering a wider view of the places he found himself in, they not only take us back to the places we once knew but also immerse us into the scene being captured. The photographs are for me, a means to travel back in time, back to the places I could otherwise have little hope of seeing again, and back to a world I would not otherwise have been able to go home to.

A street that once came alive in the evenings with its food offerings – the section of Albert Street at its Selegie Road end where Albert Court Hotel is today (David Ayres on Flickr).

An “Ice Water Stall” outside what is today the National Museum (David Ayres on Flickr).

The gate post and the Indian Rubber tree today. The tree has since gained the status of a protected tree, having been listed as one of Singapore’s 256 Heritage Trees.

Changi Creek, 1966 (David Ayres on Flickr).

Changi Creek today.

A familiar scene along Canberra Road that Mr. Ayres captured in 1966. The convoy of dockyard (and later Sembawang Shipyard) workers rushing home was seen into the 1980s (David Ayres on Flickr).

Jalan Sendudok in Sembawang. Notice that the Chinese characters used for Sembawang differ from those used today. The road, which still exists, has since been realigned (David Ayres on Flickr).

Where Selegie met Serangoon over the Rochor Canal, 1966. This photograph helps take me back to visits to Tekka market, the roof of which can be seen on the left of the photo, with my mother whenever mutton curry was on the menu (David Ayres on Flickr).

The same area today, Sans the open canal and and now unfamiliar buildings, it looks a completely different place.

1966. The North Bridge Road that I knew, close to its junction with Bras Basah Road, close to where Jubilee and Odeon Theatres were, which would have been behind the photographer (David Ayres on Flickr).

The same area today.

Further down North Bridge Road in 1966 – a back entrance to Raffles Institution is seen on the left and the walls of the former Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus (now CHIJMES) can be seen on the other side of the road (David Ayres on Flickr).

The same area today.

A river crossing in Malaysia in 1967. Not in Singapore but many from Singapore who travelled up north by road would have had this experience before road bridges across the major rivers were completed. One such crossing was at Muar. This existed up to the 1960s. My own experience was of two crossings on the road up to Kuantan in the 1970s and early 1980s. One had been at Endau, at which a tow boat similar to what is seen here was used. The other was a narrower crossing at Rompin that utilised a ferry pulled by wire-rope (David Ayres on Flickr).