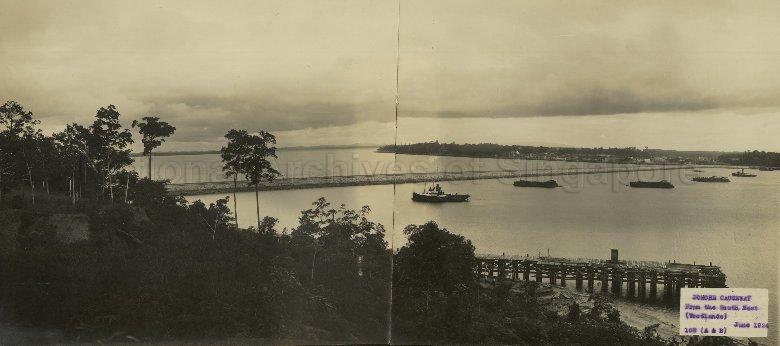

It was a hundred years ago on this very day, the 17th of September 1923, that the Causeway first came into use, when a cargo train made the crossing on tracks laid temporarily on the completed half of rubble mound which had been intended for its roadway.

Linking the island state of Singapore with Malaysia across the Straits of Johor, the one-kilometre long link is a hundred years later, one of the busiest land border crossings in the world. Hundreds of thousands cross daily with most using motor vehicles. The sheer volume of vehicles using the link does mean that traffic congestion on the Causeway and the roads leading up to it are quite a frequent occurrence, so much so that the Causeway has become synonymous with traffic jams.

It was in fact to solve the problems caused by heavy cross-strait traffic, albeit of a different kind, that the Causeway was built. It was also for the same reasons that Causeway was first made available for use by freight trains, which was a matter of urgency. The cross-strait movement of goods railway carriages had been made possible December 1909 when a wagon ferry built by the Tanjong Pagar Dock Board was put into operation, with a second added soon after. With the Johore State Railway (JSR) having been completed earlier in that same year, the wagon ferries permitted whole railway freight carriages to be moved between Singapore and the parts of the Malay Peninsula that the JSR and other lines that it was connected with.

Fed by the growing demand for rubber in the 1910s, the volume of rail carriages carried across the strait by wagon ferry grew by leaps and bounds. In 1911, some 11,500 carriages were being carried across the strait. By 1917, cross-strait cargo wagon traffic grew five-fold with some 54,000 carriages were moved by the ferries. Carrying six freight carriages at any one time, the ferries were made to operate continuously day and night to cope with the demand, which put a huge strain on them. On the recommendation of Mr P A Anthony, the General Manager of the Federated Malay States Railway or FMSR (which had absorbed the JSR and the Singapore Government Railway by that time), a decision was taken to construct a link.

While a bridge across the strait might have been a desirable outcome, the relative ease with which a rubble causeway could be constructed and maintained together with the associated savings in cost, pushed the decision towards a causeway. Designed by consulting engineers Coode, Fitzmaurice, Wlison and Mitchell and constructed by Topham, Jones and Railton, work on the Causeway commenced in April 1920. The large amounts of granite that was required, came from either quarries in Bukit Timah, or the island of Pulau Ubin. Granite from Pulau Ubin could quite conveniently be transported by hopper barge and dumped directly on site and it was from the island that the bulk of the material came from.

With granite coming by barge from Pulau Ubin, the Causeway could only be finished west to east once the gap was closed, meaning that the roadway side of its width was completed before its railway side. It was for this reason that temporary tracks were laid to permit the freight trains to use the link first. Two weeks after the link for cargo trains was established, passenger trains followed, with the first passenger train, an overnight mail train from Kuala Lumpur being the first to cross on 1st October 1923. The Causeway would only open to road traffic more than half a year later, following its completion and rescheduled official opening on the 28th of June 1924, with the very first car to cross carrying the Governor of the Straits Settlements Sir Laurence Guillemard, and Sultan Ibrahim of Johore.

Completed at a cost of 6.5 million Straits Dollars, three quarters of which was borne by the FMSR, some 1.5 million cubic yards (1.15 million cubic metres) of granite was used to build the 60 feet wide and 3465 feet long link. A feature of the newly completed Causeway which is no longer seen was a 50′ wide and with a 32′ clear span rolling lift bridge, and a 170 feet long lock with a width of 32 feet at the gates. Running across the Johore end of the Causeway, the lock permitted the east-west passage of small vessels such as fishing craft with the bridge fitted to cross the gap. The lock and bridge were deliberately destroyed by British-led forces as they withdrew from Malaya into Singapore on 31 January 1942 (with a 70′ gap was also blown in the Causeway). Along with the lock, ten 5 feet diameter culverts were also built into the Causeway, which allowed water to flow across the width of the link and prevented the accumulation of rubbish. The culverts, several of which were destroyed during the British January 1942 withdrawal, are now mostly out of action.

The “Causeway jam” does seem to have been a perennial problem. Just two years after it opened to road traffic, the first traffic jams were reported. The jams were due to the digging up of sections of the roadway so that a pipeline to carry water from the intended Gunong Pulai Reservoir to Singapore could be laid. The post-Second World War era would see much greater traffic snarls. In 1948, increased security checks (due to the Malayan Emergency), saw to traffic hold ups. The traffic situation on the Causeway seemed to worsen through the next decade. In 1950, crowds heading to the Johore Grand Prix were reported to have caused a 3-mile (5 kilometre) traffic jam, which resulted in the start of the races being delayed. A “monster traffic jam” on 17 September 1955 — the 32nd anniversary of the Causeway’s first use following Sultan Ibrahim’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations resulted in 10,000 people being stranded in Johor Bahru. Festive traffic also caused traffic hold-ups, with “chaotic scenes” on the Causeway being reported during the Chinese New Year in 1959. As a result of increasing demands, the Causeway has been widened on several occasions starting with a 1.5 metre increase in its width in 1964.

The appearance of the new Customs Checkpoint at the JB end in 1957 — just in time for Malaya’s independence from Britain, would be a sign of things to come. With Singapore and Malaya being pulled in opposite directions following a brief merger that ended with Singapore’s independence in 1965, immigration controls became necessary. It was however only in 1967 that full immigration controls were implemented — on 1st July 1967 by Singapore and on 1st September 1967 by Malaysia.

In 1998, a second link was opened across the strait. While this might have gone some way to ease the load on the Causeway, the sheer growth in cross-strait traffic now sees regular jams taking place on both crossings. In March 2020, the Causeway (and the Second Link) did however fall silent. This was a result of the border closures due to the global pandemic. The links were only reopened on 1 April 2022.

Now one hundred years later, a third crossing is being established in the form of the Rapid Transit Link or RTS, a light rail line that will be carried over a 25 metre high bridge across the strait between Singapore’s Woodlands North MRT Station and Bukit Chagar in Johor Bahru. When completed in 2026, the RTS will replace the conventional railway (now reduced to the rail shuttle service between JB and Singapore run by Keretapi Tanah Melayu). And with that, Singapore’s twelve-decade long association with the conventional railway, and a hundred year conventional railway link with the Malay Peninsula — the Causeway’s original raison d’être, will be brought to a close.

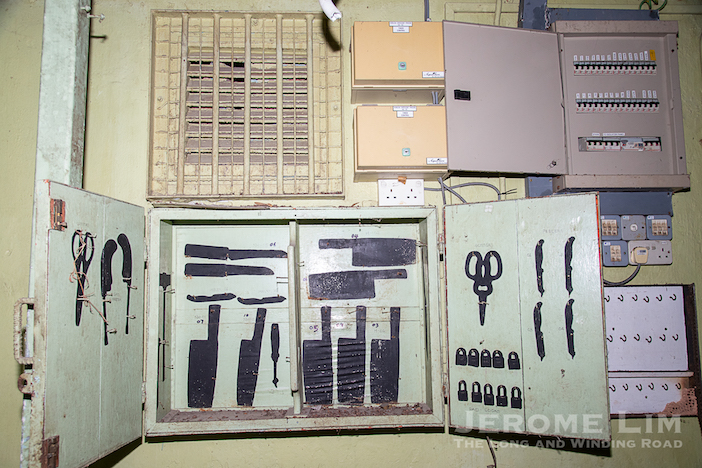

Thought to have been completed just prior to the outbreak of war in late 1941, it is also known that the building was put to use as accommodation for Asian policemen (with the Naval Base Police Force) and their families from the end of the 1950s to around 1972. During this time, the Gurdwara Sabha Naval Police – a Sikh temple, operated on the grounds. As View Road Lodge, the building was re-purposed on two occasions as a foreign workers dormitory.

Thought to have been completed just prior to the outbreak of war in late 1941, it is also known that the building was put to use as accommodation for Asian policemen (with the Naval Base Police Force) and their families from the end of the 1950s to around 1972. During this time, the Gurdwara Sabha Naval Police – a Sikh temple, operated on the grounds. As View Road Lodge, the building was re-purposed on two occasions as a foreign workers dormitory.