Street names in Singapore often hold clues to the past. Names such as “Telok Ayer Street” and “Beach Road” for example, provide an indication of where the city’s original shoreline might have been. And just as there was originally a “telok” or bay along which Telok Ayer Street ran, there was also a beach by Beach Road.

Among the questions that come to mind are: what did the beach look like, and how far did the beach stretch? Well, we do know for a start that the beach was pleasant enough for Raffles to have the stretch along the beach reserved for the dwellings of the new settlement’s elite residents as part of the European section of town (see: Middle Road and the (un)European Town). Known as the “street of twenty houses” in the vernacular, a row of twenty large compound houses did actually take up the prime stretch of Beach Road fronting the beach.

To address the first question as to what did the beach look like, we do fortunately have more than just textual descriptions of it. A visual representation of the beach can be found in a sketch from 1847 that was made by Government Surveyor John Turnbull Thomson. Titled “View from Campong Glam”, the sketch shows a sandy beach with identifiable buildings such as The Arts House (ex-Parliament House and then Public Offices / Courthouse) and the former Raffles Institution.

As for the extent of the beach, archeological evidence does show that the beach extended from the Singapore River (as is also seen in J T Thomson’s 1847 sketch) to Kampong Gelam. Excavations carried out in 2003 by Professor John Miksic and his team in the National University of Singapore have in fact revealed the existence of a layer of pure white sand under the Padang close to St Andrews Road dating back to the 14th century — the period when Sri Tri Buana or Sang Nila Utama established a port city in Singapore. Further excavations have confirmed that this white sandy beach stretched at least to the area fronting Istana Kampong Glam (Malay Heritage Centre). What is particularly interesting is that the white sandy beach, based on Prof. Miksic’s reckoning, may be the beach that drew Sri Tri Buana to the island, which is described in the Malay Annals as one with “sand so white that it looked like a sheet of cloth”!

Among the houses for the European elite fronting the beach was house number one at which Raffles Hotel would be established in 1887. By this time, most of the compound houses along the beach had disappeared and those that remained, had taken on a shabby appearance with the well-to-do having made the move to the more comfortable interior of the island. The area had in fact already morphed into Sio Po, the Chinese lesser town with the Hainanese community having established a temple dedicated to the protector of the seas, Mazu, at Malabar Street in 1857.

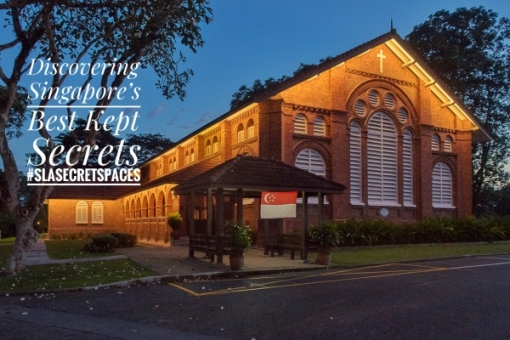

No 1 Beach Road at which Raffles Hotel was established in 1887.

It was soon after the establishment of the hotel, that it began to lose sight of the beach across Beach Road with reclamation works for what would later be known as the “Raffles Reclamation” beginning off the Esplanade — amid a blaze of rumours that sacrificial human heads were needed for work to proceed smoothly (yes, such rumours existed even then!). This would lead to an expanded Padang of the size we know today and the addition of land on the Beach Road side. By the early 1900s, the reclamation ground — which was used to dump mud dredged from the Singapore River — had become substantial enough to permit the ground to be used for polo and other sports. The old volunteer drill hall was also moved to it in early 1908 from its original site at Fort Fullerton.

The reclamation site would also be where Singapore’s first permanent cinema halls were erected. Cinema first came to Singapore in 1897, just two years after the Lumière brothers exhibited the Cinématographe in Paris. Exhibitions were held either in halls and tents before the first permanent structures appeared on the Raffles Reclamation site in the 1900s.

Further reclamation would take place through the 1930s, by which time structures such as Beach Road Camp and a newer Beach Road Police Station started to populate the reclamation site. The coastline would be altered further with the construction of Nicoll Highway in the mid-1950s and the development of what would eventually become Marina Bay, bringing us to where we are today.

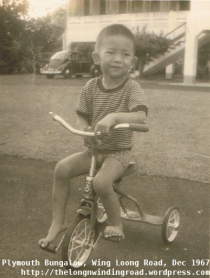

1936 view of the reclamation.