Changi Airport today has the reputation of being one of the world’s foremost airports. It wasn’t however the first airport in Singapore to win that accolade. Singapore’s very first civil airport, Kallang Airport, was in fact thought of by no less a personality as Amelia Earhart as the “peer of any in the world” when she flew into it on 20 June 1937 — just eight days after it had opened.

The streamline-moderne terminal building of the former Kallang Airport.

Kallang Aerodrome plan showing with its circular landing area, with an aerial view of the site today. The circular outline of the former airfield can still be seen.

Just like Changi, the land for Kallang Airport grew out of an area of water — a huge “pestilential fever ridden swamp” and a “plague spot of squelching mud covered only at high water” in Kallang’s case. The site, where the Geylang, Kallang and Rochor rivers spilled out into the sea, was selected as it was close to the urban centre and, well placed to receive flying boats (aircraft with boat hulls to enable landing and take-off on water) — then the mainstay of luxury travel and the airmail service.

Work proper to reclaim the swamp commences in 1932 and was on completed in 1936. The reclamation involved some eight million tons of soil obtained from Paya Lebar and created some 137 ha of land much of which was a circular landing area to permit landing from all directions — a feature found in the modern aerodromes of the era. This circular outline is still in existence today. A flying boat ramp and slipway (which was more recently used as part of the since vacated Police Coast Guard repair facilities) was constructed to service the flying boat service. This is still in existence today. The jewel in the new aerodrome’s crown was perhaps its gorgeous streamline-moderne terminal building. Designed by PWD architect Frank Dorrington Ward, who also designed the old Supreme Court, the terminal resembles a bi-plane. Used by the People’s Association as its headquarters from 1960 until 2009, the building is now one of several structures belonging to the former airport that has been conserved.

A conserved hangar.

The first regular air services into Singapore

While Kallang may have been Singapore’s first civil airport, the first regular commercial flights actually operated out of RAF Seletar – when that was completed in 1930. That was operated by KNILM — Koninklijke Nederlandsch-Indische Luchtvaart Maatschappij or Royal Dutch East Indies Airway, which inaugurated a weekly Batavia-Palembang-Singapore service on 4 March of that year. Singapore would have to wait until 1933 before it saw the first London-bound flights. This was operated by KLM (Royal Dutch Airlines) flying from Batavia with a Fokker F-XVIII. The outbound journey took seven days and inbound eight days. Imperial Airways — one of the parent companies of the present day British Airways also commenced regular services to and from London later in the same year. The one-way journey took about ten days.

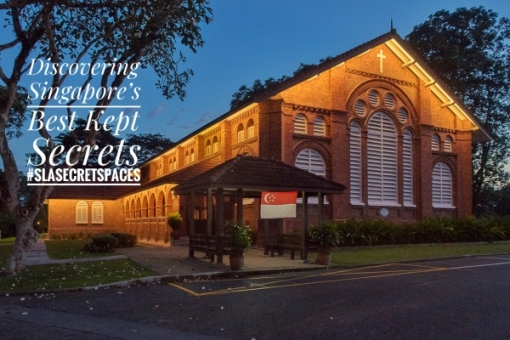

Up on the roof of the former terminal during a #SLASecretSpaces guided visit (photo : Stanley Chee).

Kallang Airport’s runway

Originally equipped with an unpaved landing area — aircraft tended to be small and light in the early days of aviation, Kallang Airport was equipped with a paved landing strip during the Japanese Occupation (it was used as a fighter airfield by the Allies in the lead up to the Fall of Singapore). This went some way in preparing the airport to receive the postwar airliners and the first ever jetliner to land in Singapore — first on a strengthened version of the Japanese-laid runway and then in 1951 on an extended version of it (into what is today Old Airport Road).

The arrival of the jet-age

While Kallang may have heralded the arrival of the jet-age to Singapore with the landing of the BOAC De Havilland Comet on a test flight, its runway was however deemed inadequate and regular jetliner services, which we started in October 1952, used RAF Changi to land and take-off from — with arriving and departing passengers bussed to and from the terminal at Kallang Airport. The use of jetliners reduced travel time to less that one-day, when it would have taken at about two days on the modern propeller powered aircraft of those days.

The control tower.

The BOAC Constellation crash

By the time of the arrival of the first regular Comets, a decision had been taken to build a new civil airport in Paya Lebar with work on it starting early in 1952 — a decision was taken none too soon as Kallang’s deficiencies were clearly exposed when on 13 March 1954, a BOAC Super Constellation hit a seawall on landing. The inquest into the crash, which killed 33, blamed the crash on pilot error. The inadequate ground support and response in both equipment and trained personnel was however, also cited as a reason for the high death toll.

A view of the terminal from the West Block.

Last flights

Kallang Airport would see its last regular flight on 21 August 1955 when Paya Lebar Airport opened. Its last plane – which had been undergoing repairs – would however, only be able to depart on 14 October. The closure of Kallang, allowed the construction of Nicoll Highway — a much needed arterial road into the city, which was completed the following year in 1956 (see: The treble-carriageway by the Promenade).

The terminal building as People’s Association HQ, 1960 to 2009.

The Main Hall

Although modestly proportioned by the standards of today, the terminal building’s Main Hall would have been its the main feature.

The Main Hall.

Occupying a double-volume space, it was designed to resemble the main hall of a railway station. In the space, offices for operating companies and a post office could be found with “accommodation for outgoing and incoming traffic”. There were also offices for immigration and customs, and medical services with a refreshment room and bar, and waiting rooms arranged. The main hall was naturally lit by a clerestory above the second level.

The main hall, seen from the second storey today.

Amelia Earhart on Singapore and Kallang Airport

Amelia Earhart, the first female pilot to fly solo across the Atlantic, landed at Kallang Aerodrome on the evening of 20 June 1937 – just eight days after it opened. The flight was part of an attempt by Ms Earhart to become the first aviatrix to circumnavigate the Earth. Ms Earhart was clearly impressed with Singapore and its new airport. In her diary entry, which she had sent back, she had this to say:

Amelia Earhart, the first female pilot to fly solo across the Atlantic, landed at Kallang Aerodrome on the evening of 20 June 1937 – just eight days after it opened. The flight was part of an attempt by Ms Earhart to become the first aviatrix to circumnavigate the Earth. Ms Earhart was clearly impressed with Singapore and its new airport. In her diary entry, which she had sent back, she had this to say:

“Then Singapore. The vast city lies on an island, the broad expanses of its famous harbour filled, as I saw them from aloft that afternoon, with little water bugs, ships of all kinds from every port.

Below us, an aviation miracle of the East, lay the magnificent new airport, the peer of any in the world. As a reminder that this was indeed the East when I shut off the engines, music from a nearby Chinese theatre floated up to greet us. West is West, and East is certainly East. The barren margins of our isolated Western airports could scarcely assimilate such urban frivolities.

From the standpoint of military strategy, Singapore holds a predominant position in the Far East. Today, less than 100 years old, it is the tenth seaport city in the world. Yesterday it was a jungle, its mangrove swamps shared by savage Malay fishermen, tigers and pythons; today it is the crossroad of trade with Europe, Africa, India, Australia, China, and Japan. Tin and rubber are the mainstays of its export”.

Sadly, the Lockheed Electra with Ms Earhart and navigator Fred Noonan, disappeared over the South Pacific on 2 July 1937 less than two weeks after her departure from Singapore early on 21 June 1937 for Bandung.

Flying Boats at Kallang

Flying Boats with their more voluminous airframes and ability to land anywhere where there was a sufficiently large and clear body of water, carried air mail and provided for luxurious air travel. A one-way journey from London to Singapore back then would have taken as long as ten days with multiple stops and cost in the region of SGD 22,000 in today’s money.

A Short Empire Flying Boat taxiing on the water “runway” off Kallang for take off, c. 1941.

Besides services to Europe, there were also trans-Pacific flights. Pan Am introduced a fortnightly service from San Francisco to Singapore in 1941, with stops at Honolulu, Midway, Wake, Guam and Manila. A one-way ticket cost US$825 – the equivalent of just over SGD 20,000 in 2020 terms.

A Pan Am Clipper flying boat off Kallang.

Commercial flying boat services to Kallang Airport ceased in 1949.

Amelia Earhart, the first female pilot to fly solo across the Atlantic, landed at Kallang Aerodrome on the evening of 20 June 1937 – just eight days after it opened. The flight was part of an attempt by Ms Earhart to become the first aviatrix to circumnavigate the Earth. Ms Earhart was clearly impressed with Singapore and its new airport. In her diary entry, which she had sent back, she had this to say:

Amelia Earhart, the first female pilot to fly solo across the Atlantic, landed at Kallang Aerodrome on the evening of 20 June 1937 – just eight days after it opened. The flight was part of an attempt by Ms Earhart to become the first aviatrix to circumnavigate the Earth. Ms Earhart was clearly impressed with Singapore and its new airport. In her diary entry, which she had sent back, she had this to say: